- Home

- Paul Fleischman

Saturnalia Page 8

Saturnalia Read online

Page 8

She strode toward her wardrobe to select a new gown, then noticed the box on her dressing table. She took up the card that lay on top. “‘With the special compliments of Samuel Hogwood, wigmaker, King Street, Boston,’” she recited.

As if he’d just heard his entrance line read, Mr. Hogwood, eyes bright, climbed painfully to his feet and cleared his throat.

“What can that pompous little pumpkin want with me now?” she asked aloud. She whirled about. “Giles! See to it that the male servants’ wigs are henceforth dressed at Mr. Swanton’s shop!”

The wigmaker’s words once again fled his mouth.

“And instruct the others to accept no further crushed oranges, foul-smelling books, battered lockets, or other endearments from Mr. Hogwood or his ill-bred man!”

The wigmaker’s baffled brains churned in his head. Crushed? Foul-smeIling? Battered? Then he knew. It was Malcolm who’d delivered each of those gifts! The rogue had opposed his courtship, fearing to be placed beneath a mistress so strict, and had cunningly led Madam Phipp to loathe him!

“Further,” she barked, “make it known that the odious hair butcher is not to be admitted to the house!” She glared at Mr. Hogwood.

“Yes, Madam,” he acknowledged, unable to free himself from his role. He turned his eyes from her. All was lost! The woman utterly despised him! He pictured the revenge he would wreak upon Malcolm. Then he thought of the gift within the box. Perhaps there was hope for him after all! The sight of silver might change her heart. He’d reveal himself, to her surprise and delight. She’d weep, pleading for his forgiveness. The sugar bowl, symbol of sweetness, would seal their vows to marry!

Mr. Hogwood approached. He cleared his throat and again readied his revelation. But before he’d a chance to speak his first word, Madam Phipp opened the box—and gasped. Her eyelids, hair, and body shot upward. She expelled a shriek that shook the windows. Open-mouthed and mystified, Mr. Hogwood sprang forward, peered into the box, and found the freshly severed head of a mouse sitting in the sugar bowl.

“With Mr. Hogwood’s special compliments!” the widow shouted out.

The wigmaker froze. It was Dan, his nephew! He’d repeatedly ordered his helpers to rid the shop of the heads Charity left. But only a scamp with Dan’s shortage of wits would toss one into a box without looking!

“I’ll see the fiend flogged for this!” raged Madam Phipp.

Mr. Hogwood, knowing his case was lost, backed away from the woman, then noticed her reach to remove her eyeglasses. Petrified now at being found out, unable to bear such embarrassment and fearful she’d scatter his brains with the poker, he flew toward the window, raised it, and leaped out onto the limb he’d entered by. His sudden weight causing it to snap, he plunged like a meteor onto Malcolm just as Madam Phipp’s serving girl was tossing a pan of hot meat drippings on him—which sizzling liquid caused the tangle of arms and legs flailing in the snow to quickly divide into two separate figures, who freed themselves from the fallen branch, frantically climbed to their knees, then their feet, then bolted down the walk and through the streets, furiously cursing each other.

Shortly past eight that evening, on Middle Street, a woman’s scream slit the winter air. Mr. Trulliber, the night watchman, heard it and hurried his legs in that direction. Tut heard it and brought his eye down from the stars. Those who lived in the neighborhood cocked their ears, as if waiting for more. Those abroad in its streets and alleys stilled their feet, among them William.

He listened a moment, then continued on briskly. He’d been sent forth by Gwenne’s royal command to find a raven’s fallen feather, an all-but-impossible task at night. Seizing his chance to leave the house, he’d filled his pockets with scraps from the noontime feast and scurried out the door. Passing Dock Square, he’d turned toward Middle Street. It was a route he’d followed often of late. For the past three nights he’d slipped out the rear door after the Curries were safely asleep. Bringing what food he could to Michamauk, he’d stayed to receive from him in return the history and lore of their tribe. At the old man’s request, then eagerly, he’d heard how Cautantowwit, the creator, had fashioned the first man and woman from stone, how a crow flew from his field with the first seeds of corn and beans and brought them to men, how the souls of the virtuous live in his house far away to the southwest. He heard of the deeds of the giant, Wetucks, and of Hobbomauk, the god who wandered at night, spreading evil and disease. Some of this he recalled from long before. But Michamauk had been a healer, a powwow, and on the night just past, once Ninnomi was sleeping, he’d told William things he’d never heard spoken, secrets meant only to be passed to a male: how to cure the sick, bring rain, see the future, how powwows of great power long ago could call mists into being at will, had caused water to burn and trees to dance. Fearing his knowledge would die with him, his great-uncle had kept him almost until dawn, burdened by how much remained to impart. The apprentice engraved all he heard in his memory. Though he’d lost Cancasset, his search for his brother had led him to happen upon Michamauk, who’d come to seem, over the course of these nights, nearly as important to him.

He marched through Middle Street’s crusted snow. Shivering in the sky, all the multitudinous stars in the heavens were gathered, as if in public celebration of this longest night of the year. He passed a baker’s, a hatter’s, a hornsmith’s, then halted at the sight of Mr. Rudd’s. A crowd was clustered before his door. Lantern beams flickered and darted like fireflies. William stopped, thought of the scream he’d heard, then charged ahead.

“Outside, I pray you!” Mr. Trulliber bellowed.

A half dozen onlookers backed down the shop’s steps. Slithering through the crowd like a snake, William gained a place near the front and managed to bend his head around the door. Three lamps sat upon the sand-strewn floor. By their light he beheld Mr. Rudd, on his back. His teeth were clamped upon a sheet of paper.

His awl, the long cord of which still circled his neck, had been driven into his heart.

William’s eyes froze upon the sight. Then he felt a hand on his shoulder, turned, and found Michamauk and Ninnomi behind him, their faces filled with fear.

“Read out what’s upon the paper!” cried a voice.

Mr. Trulliber, anxious to study it also, was more anxious still to show that the examination of the scene was his own and would not be directed by spectators. He surveyed Mr. Rudd’s workbench, then his tools, then his lamp, still burning. He pondered the footprints left in the sand. He stood before the hearth’s hissing coals as if taking their testimony. Seemingly as an afterthought, he stooped, viewed the corpse, and tugged the paper from between its possessive teeth.

He lifted a lantern and glanced at the sheet. “’Tis no more than an apprenticeship contract.”

This news was digested, noisily, by the crowd.

Mr. Trulliber brought the page closer to his face. “With Mr. Rudd’s own name written in as the apprentice,” he added in puzzlement. His eyes traveled further through the form. “And ‘eternity’ given as the term of service.” Apprehensively, he read further. “And with the master’s name given”—he looked up—”as ‘Satan.’”

William was aware of jostling behind him.

“’Twas his tawnies!” yelled a woman.

The apprentice was startled to see two men wrestling with Michamauk. William vainly struggled against them.

“Murderous, devil-worshipping wretch!”

“To the gallows with him!”

“And the girl as well!”

The men pinned Michamauk’s arms behind him. Ninnomi, frightened, attempted to flee and was snatched off her feet by a brawny blacksmith.

“’Tis Mr. Rudd’s redman, is it?” The watchman pointed his finger at Michamauk.

“Yes, sir!” came a shout. “And innocent of the crime!” The words had come from William’s mouth.

Mr. Trulliber shone his light upon

him. “And how come you to be so certain of this?” he skeptically inquired.

“The contract!” replied William. “’Twas written upon. Yet neither of Mr. Rudd’s Indians have been taught to hold a pen!”

Mr. Trulliber’s doubtful smirk departed. Murmurs filled the air, as from a throng of restless dreamers.

“Perhaps they never learned to write,” a voice commanded all ears. “But you have!”

William turned and found several lanterns trained on the fierce-eyed Mr. Baggot. Like a hovering hawk, the tithingman gripped the printer’s apprentice with his gaze and sliced toward him through the gathering.

“In faith, your penmanship is peerless!” he praised him to his face. “As befits a boy of your fine education, tutored as Mr. Currie has seen fit. A lad who can converse in Latin, read in Greek, and whose memory of Scripture mocks the town tithingmen’s own.”

Mr. Baggot smiled at his accomplished student. “But there’s more to the boy!” he declared to the others. “He’s a Narraganset, like Mr. Rudd’s. Indeed, the three be related, I’ve discovered!”

Mr. Trulliber, who felt that discovering was properly in his domain, stared at the speaker disapprovingly.

“Mr. Rudd, as ’tis known, was not a soft man.” The tithingman eyed Michamauk and Ninnomi. “His tawnies no doubt complained to their kinsman. The knave turned his villainous brains to the matter. And for four nights past has he lifted his gullible master’s latch, as the redmen do well, and skulked through the streets to this very house—with me following behind!”

Astounded, William gawked at the man. His mind went utterly blank for a moment. He felt chilled, both from the cold and his fright. Then his senses returned, he reached into a pocket, and pulled out a heel of pumpkin bread.

“To keep them from starving!” he shouted out, holding it up for all to see.

“To plot the murder of an upstanding Christian!” the tithingman retorted.

A man stepped forward, lantern in hand. “Mr. Currie’s William? ’Tis past belief!”

“Hell-hatched demon!” his neighbor disagreed.

Mr. Trulliber focused his eyes on a line at the bottom of the apprenticeship contract. “‘Sold by Charles Currie, printer, King Street, Boston,’” he read aloud.

Victoriously, Mr. Baggot eyed William. “Snared!” he proclaimed. “Just as I vowed!” He grasped the boy’s arm with his shacklelike hand. “The serpent’s shed his English skin, and shown himself a Satan-loving savage! Mr. Currie was lucky ’twasn’t him murdered!”

The mention of his master widened William’s eyes.

“Pray, sir, let loose!” With a mighty tug, he freed himself from the tithingman, shot up the shop’s steps, and asked to look at the contract for himself. By the watchman’s light, he made out the line that Mr. Trulliber had just read out. The form had indeed been purchased at his shop. He studied the words that had been written in. The penmanship was not his. And though he didn’t know whose it was, he felt suddenly certain that he’d laid eyes on the person. Hadn’t he recently sold such a form, to a man so bundled he could scarcely be seen? A humming man, who’d peered strangely at William, as if in recognition?

“Enough! Seize the blood-drinking brute!” the tithingman ordered Mr. Trulliber.

“A moment!” William looked up from the contract and glanced about the eyeglass maker’s shop. On one wall was posted a line of advertisements for the man’s lengthy lineage of runaways. These too had been printed at Mr. Currie’s. Scanning the row, his eyes halted upon a gap midway down the wall. He’d never heard of any of Mr. Rudd’s apprentices being caught and returned. One of the notices had been removed.

“But of course!” he burst forth. “’Twas one of the man’s apprentices! I saw him myself, and sold him a contract just such as this!” He spun toward Mr. Trulliber. “Perhaps five days past! A thin man. His eyes green.” He picked up a lamp, rushed over to the wall, and struggled to raise from his memory the name of the apprentice who’d scampered off between Jacob Fox and Samuel Stinchcombe.

“The boy speaks lies!” roared Mr. Baggot. “He only hopes to wriggle out of his noose. Watchman, to the prison with him!”

Mr. Trulliber, scowling at the meddling tithingman, ignored him on principle.

“Gideon Smeed!” cried William. “That’s the name! I set the type for the notice myself!” He reached back into his memory. He faced the wall and shut his eyes. He tried to exclude all sound from his ears.

“‘Dashed off the eighth night of March,’” he recited. “‘His left print larger than his right. Both of them likely leading to Hell.’”

“Will the word of a sneaking tawny outweigh a tithingman’s?” Mr. Baggot stormed.

“Clap the cur in chains!” boomed a man.

The apprentice appealed to Mr. Trulliber. “Surely you recollect Gideon! He’d seven toes upon one foot. For which cause Mr. Rudd swore he was fathered by the Devil and flogged him at his whim.”

“And one night cut the lad full across his forehead with his awl,” spoke a woman.

William recalled the low-brimmed hat the runaway had worn that day, so low it nearly rested on his nose.

“Of what import is this?” fumed Mr. Baggot.

“Suppose the boy be lying!” called a voice.

William looked back into the shop, then scurried toward the notices. He snatched from the floor a scrap of paper, eyed it, and gave it to Mr. Trulliber, who gravely studied it by his light.

“’Twould appear to be a piece of a runaway notice torn from Mr. Rudd’s wall. Containing the name of Gideon Smeed.” The watchman raised his eyes from the scrap. “He likely hoped he’d be forgotten by snatching his notice. And was remembered instead.”

William gazed upon Mr. Baggot. For the second time in a week his memory had thwarted the tithingman.

“Will justice be gulled by the boy?” the man raged.

“Silence!” demanded the watchman, drained of patience with Mr. Baggot. Determined to reclaim control of the proceedings, he tucked the scrap of paper in a pocket, then was struck by a thought. He turned and looked down at the eyeglass maker. His lantern trained upon the floor, he then slowly trod about the room, slipped from sight down a narrow hallway, and eventually reappeared outside the shop at the rear of the crowd.

“The boy speaks God’s truth,” Mr. Trulliber announced. “There’s a trail of footprints left in the sand, with the left foot larger than the right. Plain to read as bear tracks beneath a bee tree. A trail that I warrant already leads out to the Neck and through the town gate.”

William turned a triumphant smile on the stonefaced tithingman. Buzzing, the spectators began to disperse, carrying the news to their various hearths.

“But the rogue was abroad past curfew,” Mr. Baggot thundered above the surrounding hubbub. “Surely he must be punished for that!”

The watchman approached him disdainfully. “’Twas from mercy and therefore pardonable,” he pronounced, from spite for Mr. Baggot and respect for William, who apparently was not one of the yawners, but was rather a lad who, like himself, could ignore the call of sleep, who knew the night. ’Twas Mr. Rudd deserved to be punished, for ill-using his servants. As it appears he was. And as you shall be also should you not leave this matter to me, as is meet. To your bed, with the rest!”

Mr. Baggot glared at the watchman, then at William. Then he whirled furiously and stalked off.

Two onlookers chuckled. William watched the man vanish. Then he found Michamauk and Ninnomi and followed them to their shed. Their faces were glum.

“What will become of us now?” the girl asked William in Narraganset.

“I’m not certain,” he answered her, soft-voiced. “Perhaps you’ll be given to another master.”

Michamauk shook his head. “No, Weetasket. Tonight we shall leave.”

William’s heart paused, then sped in compensat

ion.

“Six years among the coatmen is enough. We’re free tonight. Why should we wait and find ourselves slaves once more in the morning?” He lit a twig at his lamp and transferred the flame to his stone pipe. “Two days’ walking west of our old home, I’m told, our people can be found. Where Ninnomi will find a woman to teach her. And, later, a husband.”

“You’ll be caught!” spoke William. “Boston Neck is narrow. All must pass that way. And the

guards at the gate will have their eyes open, looking for Gideon Smeed.”

Michamauk seemed unworried. “I have also been told that the past four days’ cold has frozen the Charles River.” He puffed on his pipe and smiled. “Like the English soldiers, we will walk on the ice.”

William considered. “But what will I do? I also have much more to learn. From you.”

Michamauk stared at the apprentice. “Come with us.”

SEVEN

THE SUN ROSE WITH LORDLY SPLENDOR the next morning, searing the clouds and gilding the waters, driving the darkness before it toward the west, breaking the night’s long siege.

At Madam Phipp’s, the widow announced to her servants that Mr. John Sharpe, a shipowner of means, would shortly become their new master. Following this, she offered a curt apology to Giles, her footman, for her severity the previous evening, which repentance he accepted in bafflement. At Mr. Hogwood’s, the wigmaker wasted no such contrition on Malcolm or his nephew, Dan, both of whom he’d belabored with a poker until the wounds to his arm, back, and hands inflicted by Madam Phipp had finally forced him to cease. Across Dock Square, Mr. Speke’s door was rapped upon by Mr. Rudd’s niece, who engaged the carver to build a coffin, adding the news that her uncle’s Indians had apparently dashed off during the night. Silently, Mr. Speke wished them well.

At Mr. Currie’s, the household was returned right side up. Sarah fetched the morning’s water. James fed the fowls. Gwenne filled lamps. And William kindled the house’s fires, his thoughts fixed on Michamauk and Ninnomi.

Joyful Noise

Joyful Noise The Half-a-Moon Inn

The Half-a-Moon Inn Rear-View Mirrors

Rear-View Mirrors Saturnalia

Saturnalia Zap

Zap Graven Images

Graven Images A Fate Totally Worse Than Death

A Fate Totally Worse Than Death Whirligig

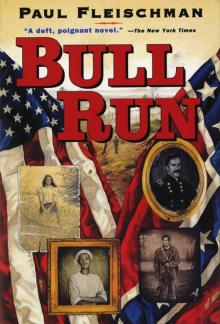

Whirligig Bull Run

Bull Run