- Home

- Paul Fleischman

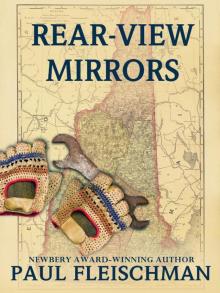

Rear-View Mirrors

Rear-View Mirrors Read online

Rear-View Mirrors

PAUL FLEISCHMAN

Rear-View Mirrors: West meets east and city meets country when a 17-year old Californian, Olivia, spends a summer with her estranged father in New Hampshire and finds out that she’s more than her mother’s daughter.

***

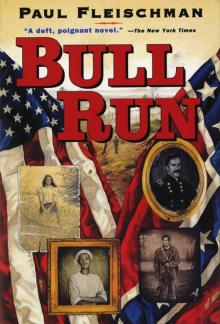

Paul Fleischman grew up in Santa Monica, California, the son of children's book author Sid Fleischman. Drawing on history, music, art, and theater, his books have often experimented with multiple viewpoints and performance. He received the Newbery Medal in 1989 for JOYFUL NOISE: POEMS FOR TWO VOICES, a Newbery Honor Award for GRAVEN IMAGES, the Scott O'Dell Award for Historical Fiction for BULL RUN, and was a National Book Award finalist for BREAKOUT. He lives on the central coast of California. His horror parody A FATE TOTALLY WORSE THAN DEATH is also available as an AudioGO ebook.

For David Brooks and Jennifer Jany

Rear-View Mirrors

Copyright © 1986 by Paul Fleischman

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

First ebook edition 2012 by AudioGO. All Rights Reserved.

Trade ISBN 978-1-62064-392-1

Library ISBN 978-0-7927-9447-9

Cover illustration © gokcen yener/iStock.com.

Table of Contents

1 / Mailbox

2 / Whippoorwill

3 / Butterflies

4 / Pie Tin

5 / Epitaph

6 / Jukebox

7 / Girl With Goat

8 / Sphinx Moths

Rear-View Mirrors

1 / Mailbox

I grew up acquainted with my father neither by sight nor by scent, but solely by report. He was like a distant land known only through travelers’ tales, an inhospitable realm where strange and shocking customs survived. There, moths and butterflies were stalked, caught, dried, labeled, and displayed on the walls of every room, as if they were charms against evil spirits. Pea soup and bagels were the staple foods. The Boston Red Sox were noisily worshipped there and the tobacco leaf ritually burned, its foul-smelling smoke, unknown in our house, constantly rising upward like incense. My mother had been there, carrying me out of that country when I was eight months old. As my father, in the sixteen years after, hadn’t found time to once call or write, I grew up to be grateful she’d taken me with her. She was his ex-wife; I was his ex-daughter.

I’ve found myself musing on all of this while making my way down Hatfield Road. I gaze out across the field to my left, hear a meadowlark singing, smell freshly cut hay, amazed by my present circumstances: to be strolling at dusk in North Hooton, New Hampshire, having started the day in Berkeley, California; to be in my father’s town, walking down his road, heading intentionally toward his house, a destination I’d long vowed to avoid; to find the sight of the “Eggs” sign ahead and the row of sugar maples to my right not only familiar, but welcome. For this is my second trip here. My first was a year ago. In the interim, my father was killed by lightning while up on his roof, replacing shingles in a storm. I pass a beech tree, study the trunk, and remember what he said about beeches. The road is lined with such rear-view mirrors in which I behold the summer before. I round a curve, then pass by a mailbox—and at once think back a year, to his letter.

***

It was after my next-to-last day of eleventh grade that my mother came home from work and delivered it to me.

“Letter for Miss Tate!”

She announced this like a town crier, but seemed slightly anxious underneath her good cheer. I studied the envelope. It was addressed to me, in care of my mother, in care of the Sociology Department, University of California. In the corner was a return address in some town I’d never heard of in New Hampshire.

I peered down at the postmark, then up at my mother. “But I don’t know a soul in New Hampshire.”

“Been writing your address in telephone booths?” She fiddled nervously with an earring. “‘For a good read, write Olivia Tate, 1521 Cedar Street, Berkeley.’”

We both smiled. I thought about New Hampshire: maple syrup, snow in the winter, the first presidential primaries. But no one connected with the state came to mind.

“Olivia, dear—I’ve got a pile of papers on Lenin I have to read after dinner. If you don’t plan to open the letter by then, or want some professional help in reading it—”

I turned it over and slit it open. In the midst of which act I suddenly recalled hearing my mother speak of spending weekends, long ago, with my father at his parents’ house, somewhere in New England.

I pulled out the contents of the envelope and felt my mother bending over my shoulder. In my hand I found an airline ticket, one way, in my name, from Oakland to Boston. Beneath it, a bus ticket from Boston to North Hooton, N.H. Under that, a handwritten note:

Olivia,

Remarkable opportunity. Return trip paid. Come if you can.

Your father

My mother seemed dazed. “My God,” she murmured. “Truly remarkable.”

I stared at the unfamiliar handwriting, reread the telegram-style message, and found an old Rolling Stones song playing in my head: “Under My Thumb.” Which was where, it gradually dawned on me, I finally had my father. Begging for me to come to him. I smiled inside to realize our reversal of roles and my sudden advantage. And I decided at once on my response: Let him beg!

Five days later I was on the plane.

2 / Whippoorwill

Hatfield Road hasn’t changed in a year. I stroll past the red cottage, see the same car in the driveway, avoid the same pothole in the road. The sun is down now. The road turns to dirt. I await the sight of my father’s house, pass the Knotts’ place, and know his is next.

I walk past the pond and spot the chimney ahead. It’s June and the trees are all in full leaf. Through the veil of greenery I glimpse a bit of white wall and green shutter. Then the red front door. Then I round the big maple by the mailbox, march up the dirt driveway, and behold it whole.

The house is two-story, clapboard, white—about as rare around here as baked beans for dinner. To the left is a barn, appropriately weathered. Behind, there’s a field of weeds and wild flowers keeping the woods beyond at bay.

I take off my backpack and glance around. The barn door is padlocked. There’s no car in sight. I walk to the barn, reach my hand inside the knothole, and find that the keys are still hanging from the nail just below. I open the barn door. The bicycle is there. I sigh, relieved, and squeeze the tires. They’re soft, but should get me to the gas station. I poke around. It seems strangely quiet, then it hits me that the goat and chickens are gone. My uncle must have sold them, along with the car. Since he only comes here on weekends, and it’s a Wednesday, I don’t figure I’ll see him.

I leave the barn, pick up my pack, climb the porch steps, and unlock the front door. I flick on a light switch and step inside. The desk and chairs are where I recall them. The huge luna moth is in its place on the wall. I feel like the archaeologist Petrie, entering the tomb of a pharaoh. I walk across the room to the pump organ. I take a seat, work the wheezy pedals, and play a couple of notes. My father’s book of Duke Ellington songs is open to “Solitude”—his favorite.

I walk to the kitchen, paw through my pack, and extract a supper of dates and sardines. I find a 7-Up in the fridge. By the time I’m through eating it’s 9:15, by the clock. For me it’s 6:15. I remind myself that despite the time change I need to get to sleep early tonight. Not because I’m especially tired from traveling—but because of tomorrow.

I stroll through the house, then climb the narrow stairway. I walk down the hall and enter “my” room.

Red rocking chair, night table, bed, sphinx moths mounted above the head. Everything just as it was before, preserved as perfectly as Pompeii.

I raise the blinds and open the windows. Unrolling my sleeping bag on the bed, I find my mind, as it’s been doing all day, doubling back to the summer before. I turn out the light, undress, lie down, and reflect on the stretch between that June and this. During which time, outside of my schoolwork, I’ve pored over books on the Toltecs and Troy, Sir Arthur Evans, Schliemann, Petrie; struck flints and ground acorns like the California Indians; and arranged to work the month of July at a dig in Maine, where I’ll go in two days. After I’ve done what I came here to do.

I close my eyes but they won’t stay shut. My body knows it’s not time for sleep. Suddenly, a whippoorwill starts singing, and my mind travels back to my first night here.

***

It was dark when the bus from Boston halted. The driver twisted around in his seat and smiled in my direction. “North Hooton!”

There was no place on earth I wanted to be less. I hauled down my mother’s battered gray suitcase, wondering what I was doing here. She’d appeared to be proud of my resistance at first, then insisted I go and see my father. Perhaps because the chance might not come again. Or perhaps in hopes I wouldn’t like what I saw, bearing out her leaving him in particular and her disappointment in men in general.

Reluctantly, I shuffled down the aisle. Back in Boston I’d thought about finding someone to use my bus ticket and name and letting my father, who wouldn’t know the difference, take in a stranger for the summer. Descending the steps, I quickly realized that I couldn’t be sure what he looked like either, since the few photographs we had of him were close to twenty years old.

I stepped out into the warm evening air—and froze at the sight of a man approaching. He had a newspaper in one hand and a cigarette in the other. His eyes looked me over, then lit at the sight of the white-haired woman exiting behind me. They kissed and walked off. The bus pulled away, leaving me alone at what seemed to be North Hooton’s sole intersection.

I glanced around. I was in front of a café. The other three corners were occupied by a gas station, a post office, and a church—but no father. I leaned up against the streetlight behind me. There was no one about, no drivers slowed and stared, but I felt conspicuous just the same. And a fool for coming, when I could have passed out leaflets at a rent control rally that afternoon at which my mother was speaking. And when I could have had a paying job helping with the research for her articles, instead of wasting my time in Hicksville.

I stared up the street, looked at my watch, and wondered if the bus had been early. The mosquitoes were certainly there on time. I waved them away with my father’s letter and speculated on his tracking us down. Our phone was unlisted. He didn’t know our address. No problem for the writer of a string of crappy mysteries starring Virgil Stark, sonnet-writing private eye—books I’d proudly refused to read. He probably looked at a Berkeley catalog and found my mother still on the faculty—the same job that had sprung us free of him and New York City so long ago. I smiled to imagine him seeing her now listed as a full professor. And continued to smile at imagining his dilemma had her name not been there.

Ten minutes and a dozen mosquito bites later I was ready to hitch back to Berkeley on the spot. Then I realized I could try calling him from the café, if his number wasn’t unlisted. And if the telephone had reached North Hooton. I picked up my suitcase—then set it down at the sight of a man coming down the steps.

He had a limp and a cane and was gesturing toward me. He halted a moment and we stared at each other. He was taller than my mother, as was I. On his head was a ragged Red Sox cap. In the light of the street lamp I gazed at his filthy clothes and worn features and felt suddenly shaky. Guilt-stricken, I studied his difficult walk, amazed that I’d spent my life hating a cripple—then noticed my eyes were filling with tears, despite sixteen years of coaching to the contrary.

He approached, slowly, and peered into my face. Neither of us seemed to know what to say. Finally, he cleared his throat.

“If you’re needing a lift somewhere, young lady—”

My jaw dropped. My eyes widened.

“No need to take offense!” He retreated a step. “Only trying to be neighborly!”

I gaped at the man. “You’re not Hannibal Tate?”

His jaw dropped. He blinked. “No, ma’am.”

I wiped away my wasted tears and hoped he hadn’t noticed them.

“Floyd Peck. Live out on Hatfield Road, though. I drive right past Hal’s, if that’s where you’re headed.”

I nodded and found myself relieved to have regained a father I could safely despise. I picked up my suitcase and walked to his car, grateful for rural hospitality, wondering why my father hadn’t picked up the trait. We set off and at once were surrounded by woods. I half-expected to see wolves in our headlights, to have our tires slashed by owls, our flesh fed to their young. I was soothed to hear my driver’s voice, asking where I’d traveled from. And amused when my reply brought forth from him a summary of an article about some California feminists who’d lurked outside a liquor store, trailed home a man who’d bought a copy of Playboy, and left him hanging upside-down from a chandelier as a warning to others. Not wanting to disappoint him, I said it was true. He quickly declared that the only magazine he read was American Dairyman. I mentioned that some of the more radical bands had talked of targeting it as well. He slammed on the brakes. I thought I was going to be asked to walk the rest of the way there—but there was where we turned out to be.

“Looks like he’s home,” Mr. Peck spoke up cheerfully, anxious, it seemed, to be rid of me. Three lights were on in the house to our right. Vengefully, I pictured my father hanging by the ankles from one of them.

I retrieved my suitcase from the back seat of the car, thanked my chauffeur, and watched him drive off. Then I turned and stared at my father’s house, reluctant to finally meet the man I’d traveled so many miles to see. The evening air felt foreign to me: hot and strangely heavy. I was sweating, though whether because of the heat or out of nervousness I wasn’t sure. I stood for five minutes, then started up the driveway, not so much attracted by my father as repelled by the mosquitoes.

I climbed up the porch steps and set down my suitcase. I peered through the screen door into the living room, saw no one there, prepared to knock, then decided that that was too familiar a summons for someone who, until now, had wanted nothing to do with me, and who’d left me to wait at the bus stop besides. Taking great pleasure in treating him as the stranger he was, I rang the bell.

Footsteps sounded above. Stairs creaked. And it occurred to me that Mr. Peck might have pulled my leg as I had pulled his—and dropped me off in front of the wrong house. Which possibility, when a figure appeared, provided me with a justification for my stiffly formal greeting.

“Pardon me. But would you happen to be Mr. H. L. Tate?”

The man facing me was lit only from behind, reducing him to silhouette. “Yes, that’s right.”

I was thunderstruck. Wasn’t he going to ask me in? Astounded, I stared at the shape before me: tall, broad-shouldered, holding a pipe. Surely he knew who I was. Or did women with suitcases commonly appear on his porch? I took a deep breath, determined not to lose this duel of indifference.

“Then I suppose it was you,” I stated casually, “who didn’t meet me at the bus from Boston.”

The shape took a step back and looked at its watch.

“My goodness—you must be Olivia.”

I nodded.

“I forgot the time altogether.”

I didn’t believe him for a minute. The bastard! He’d swallowed his pride, sought me out, sent an invitation and a ticket—then turned the tables by not picking me up, forcing me to go hunting for him. Making me the seeker once again.

“I must have dozed off for an hour,” he explained.

With a lit pipe in your mouth? I asked myself. Finally,

he opened the door, and I picked up my suitcase and hauled it inside. A reunion several steps down from Stanley and Livingstone on the Great Meetings list.

“How did you get here?” my father asked.

I set down my things and turned around, seeing him for the first time in the light. And at once I felt my anger subside, overcome by the fascination of viewing my father in the flesh. Though at first sight he seemed more monument than man: massive frame, vast hands, giant feet. He was round-faced and bald, slightly flabby, and was dressed in an undershirt and checked shorts.

Each detail about him was a surprise, and my eyes flitted quickly from one to another: the bushiness of his graying eyebrows, his wire-rim glasses, the scar on one shin, the fineness of his fingers and their neatly trimmed nails. Then suddenly I recalled his question.

“A Mr. Peck drove me here,” I replied. “He said he was going out this way.”

My father thoughtfully sucked on his pipe. I noticed his eyes surveying me and couldn’t help but wonder what he thought.

“Rather on the tall side, aren’t you?” he inquired.

I was dumbstruck. Yes, I was tall. Too tall. His fault, it was now plain to see. I’d hoped for some fatherly compliment—and vowed not to let my defenses down again.

“I must say, your hair’s darkened up a good deal.” His voice was oversized and his cadence slow, as if he were an orator from the last century. “Despite all that surfing and lounging in the sun.”

“There’s no surfing on San Francisco Bay,” I shot back.

He grunted. “And how’s your mother faring? Still writing those pompous articles?”

I let this loaded question pass and noticed the papers spread around his desk. “How’s the Great American Novel coming?’’

He continued as if I hadn’t spoken. “I don’t believe that woman could say ‘Pass the salt’ without footnotes to Aristotle, Karl Marx, Julia Child, and Amy Vanderbilt.”

Joyful Noise

Joyful Noise The Half-a-Moon Inn

The Half-a-Moon Inn Rear-View Mirrors

Rear-View Mirrors Saturnalia

Saturnalia Zap

Zap Graven Images

Graven Images A Fate Totally Worse Than Death

A Fate Totally Worse Than Death Whirligig

Whirligig Bull Run

Bull Run