- Home

- Paul Fleischman

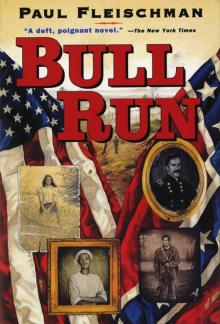

Bull Run

Bull Run Read online

MAPS

DEDICATION

For Keith and all the Swards

CONTENTS

Maps

Dedication

Colonel Oliver Brattle

Lily Malloy

Shem Suggs

Gideon Adams

Flora Wheelworth

James Dacy

Toby Boyce

Gideon Adams

Virgil Peavey

Nathaniel Epp

Shem Suggs

Dietrich Herz

Dr. William Rye

Lily Malloy

Toby Boyce

James Dacy

Judah Jenkins

General Irvin Mcdowell

Flora Wheelworth

Gideon Adams

Colonel Oliver Brattle

A. B. Tilbury

Carlotta King

Nathaniel Epp

Virgil Peavey

General Irvin Mcdowell

Shem Suggs

Gideon Adams

Flora Wheelworth

Edmund Upwing

Judah Jenkins

Dietrich Herz

Toby Boyce

James Dacy

Colonel Oliver Brattle

A. B. Tilbury

Dr. William Rye

Edmund Upwing

Virgil Peavey

Dietrich Herz

Carlotta King

Gideon Adams

Judah Jenkins

A. B. Tilbury

Shem Suggs

General Irvin Mcdowell

Toby Boyce

James Dacy

Colonel Oliver Brattle

Edmund Upwing

Carlotta King

Dietrich Herz

Shem Suggs

Nathaniel Epp

Dr. William Rye

Gideon Adams

Toby Boyce

Edmund Upwing

Flora Wheelworth

Lily Malloy

Note

Excerpt from Seedfolks

About the Author

Also by Paul Fleischman

Copyright

About the Publisher

* * *

COLONEL OLIVER BRATTLE

* * *

The booming jerked me out of sleep, woke the dishes and set them chattering, and sent Clara dashing through the dark to the children. “Must be the Lord comin’!” cried one of the servants. I realized I’d been dreaming of Mexico. Strange.

I lit a candle. The clock read four thirty. All of Charleston seemed to be in the streets. I dressed, stepped out the front door, and was embraced at once by a teary-eyed stranger. “Praise the day!” he shrieked into my face. “They’re firing on Fort Sumter!”

We gathered on Judge Frye’s flat roof. The cannons rattled the very constellations. Shells sailed, their lit fuses tracing caliper-perfect arcs, then exploded. Each illumination of the bay was greeted with appreciative oohs and hurrahs. You’d have thought that the crowds were enjoying a Fourth of July display. Some brought baskets of food to the rooftops and raised glasses in toasts to South Carolina, Jefferson Davis, and General Beauregard. I was silent, though I shared their allegiance. I’d fought, however, fourteen years before from Veracruz to Mexico City. I remembered well what shells do to living flesh, and felt in melancholy mood. Amid all the cheering, the Negroes were similarly glum—suspiciously so. If they rejoiced that a war that might break their bonds had begun, they dared let no one discern it. By a bursting shell’s light, I eyed Vernon, my body servant. He caught my glance and the slimmest of smiles fled his lips, like a snake disappearing down a hole.

* * *

LILY MALLOY

* * *

Minnesota is flat as a cracker. Rise up on your toes and you can see across the state. Scarce even a tree in sight but for a few willows beside the creeks. Father said God put willows here that man might have switches to enforce His commandments. Father was a grim-faced Scot and a great believer in switching. Each morning he put on his spectacles, without which he was all but blind. And each evening all six of us were whipped for whatever failings he’d noticed that day. If no fault could be found, we were whipped just the same for any wrongs committed out of his sight. Wee Sarah was not spared, nor Patrick, seventeen and tall. Father was taller still.

One chill April Sunday in 1861, we rode in to church and found a crowd before the door. Mr. Nilson was reading from a newspaper. Fort Sumter had been attacked. The gallant defenders had surrendered the next day. The President had called the Union to arms. That such a far-distant doing should, like a lever, shake Crow County amazed me. Mother wept. The men swore, despite the Sabbath. There was talk that a regiment of one thousand soldiers was being raised in Minnesota. Patrick’s eyes glittered like diamonds.

Reverend Bott railed against the Rebels that day. His sermon’s subject was “A man’s worst foes are those of his own household.” Father repeated the line at supper, his eyes fixed upon Patrick. That night, Father gave him a terrible thrashing. Afterward, Patrick asked the reason. “You’re thinking to scamper off!” shouted Father. “Don’t think I don’t know it! And don’t think you’ll succeed!” He stood his full height. “I can see fifty miles! I’ll hunt you like a wolf, and skin you like one!”

I didn’t think I’d sleep that night. At dawn I woke to find my hand holding an old willow whistle Patrick had fashioned. I knew then he was gone and began to cry. We were five years apart but dear to each other. How I did fear that he’d be caught. Then I heard Father roar, “And the stone-hearted rogue took my spectacles with him!”

* * *

SHEM SUGGS

* * *

Horses have always served me for kin. The first time one looked back into my eyes, I knew that I was no longer alone on this earth, orphan or no. Never had one of my own to care for. The folks I lived with kept mules. But we’d put up wayfarers crossing Arkansas. Their horses trusted me straightaway, as if they’d known me from before. I’d feed ’em and wash ’em and brush ’em and we’d talk. An hour after arriving, they’d come to me sooner than to their owners. I felt among family with ’em, and forlorn as a ghost when they’d gone.

I was boarding at Mr. Bee’s when a traveler told us about Fort Sumter. He left us a newspaper from Virginia. I was nineteen and couldn’t read a lick, but I spotted a picture of a horse. I asked Mr. Bee to read the words below. They called men to join the cavalry. Mr. Bee hated Yankees the way a broom hates dirt, and he started in again on Lincoln and the sovereign states and the constitutional right to secede. I just nodded my head like a wooden puppet, thinking about the newspaper instead. It said they’d give me a horse.

* * *

GIDEON ADAMS

* * *

Though my skin is quite light, I’m a Negro, I’m proud of it, and I wept with joy along with my brethren at President Lincoln’s call for men. How we yearned to strike a blow in the battle! Though the state of Ohio refused us the vote and discouraged us from settling, we rose to her aid just the same. No less than Cincinnati’s whites, we organized meetings, heard ringing speeches, sang “Hail Columbia” and “John Brown’s Body.” All recognized that Cincinnati was vulnerable to capture. We therefore proposed to ready a company of Home Guards, its numbers, training, and equipment to be provided by the black citizens of the city and its services offered to her defense. At last the nation’s eyes would behold the Negro’s energy and courage!

We set up two recruiting stations. They were filled at once with scores of volunteers. Cheered by this magnificent response, we planned a second meeting at a schoolhouse. Arriving, I found the building all but ringed by a crowd of clamoring whites. Many had clubs. Several were drunk. “It’s a white man’s war!” one addressed me point-blank. “You’ll do no damn parading about with guns!” I’ve tr

ied to forget the coarser things said. I inserted the key in the door’s padlock, but a police captain roughly drew it out. He announced that our meeting was canceled and our entire enterprise with it, on the grounds of inviting mob violence. “Go back to your miserable homes!” he ordered us, rather than the whites. “And stay there!”

I vowed that I would do otherwise.

* * *

FLORA WHEELWORTH

* * *

Lupine and honeysuckle bloomed as before, the oaks put out leaves, whippoorwills called. Outside it might have been any spring. But within the walls of the house it was the spring Virginia left the Union, a season separate from all before it. My three daughters came, with their families, and didn’t their needles swoop like swallows, stitching up uniforms for their husbands. All the talk was of war, and all the singing. Each night we set candles in every window, proclaiming our joy at joining the Confederacy. “Nonilluminators” were suspect.

We remarked the train whistles coming from Manassas Junction while we sewed. The day arrived when we drove our men there to send them off to war. Each daughter held up her husband’s sword and consecrated it with a kiss. Then they took their tearful farewells, and our brave knights boarded the train for Richmond, each followed by his servant. Banners flapped. A band played. Women cut buttons off their clothes and handed them through the windows as keepsakes. The church society gave the men Bibles, each inscribed with “Fight the good fight.” Girls whose beaus hadn’t joined shamed them by giving out flowers to soldiers. Finally the whistle blew. The cars moved, drawing taut and then snapping dozens of parting conversations. “Stain your sword to the hilt!” shouted the waving woman beside me. Susannah, my eldest, scurried after the train. She’d supplied her husband with razor, mirror, hairbrush, nail file, calfskin slippers, and a fine suit of clothes to be saved for his triumphant entry into Washington. “Do try not to soil the coat!” she called out.

* * *

JAMES DACY

* * *

Never was there such a send-off as that given the Sixth Massachusetts Regiment, the first to leave for Washington. Thousands saw the trains off from Boston, the cheering loud enough to stir the saints. Great geysers were shot into the air by fire trucks when the cars passed through Worcester and Springfield. In New York, the regiment marched down thronged Broadway to an elegant breakfast at the Astor House. Their gunstocks were oiled, their bayonets bright. I was traveling with them as sketch artist for the New York Illustrated News and was similarly fitted out for the conflict, armed with paper and three dozen pencils. I was to send back drawings that would let readers stand where I stood and view the war as if there, lacking naught but the singing of bullets past their ears. I’d no notion I’d hear that sound so soon.

We reached Philadelphia that night and Baltimore the following noon. We’d been warned that Baltimore was no Boston. Taking horsecars from one station to another, we were startled to see men and women wearing Confederate ribbons and rosettes. In place of cheers, we were greeted with insults. Plug-ugly toughs, spoiling for a fight, were drawn our way like moths to a light. The crowd about us thickened, grew bolder, then brazenly halted the horses. We disembarked and attempted to march. Vulgarities and vegetables were hurled. Rocks followed. Then deadly paving blocks. A Cambridge lad to my left was struck and sank upon one knee. A spectator tried to steal his musket. Then a shot rang out and a soldier just beside me fell to the ground. I’m a Boston man myself, and I snatched up the martyr’s gun, hot for revenge. The company was ordered to fire on the mob. I joined them. There were screams, and further shots. We quick-stepped through a hailstorm of stones, finally reached the Camden Street station, then had to wait for a locomotive. Three valiant volunteers were dead. Many others were injured. I burned to put upon paper the faces of the taunting traitors and the fallen heroes, took up a pencil, tried to draw—but couldn’t. My hands were shaking, with fury.

* * *

TOBY BOYCE

* * *

I was eleven years old and desperate to kill a Yankee before the supply ran out. It seemed that all Georgia had joined except me. I knew I’d never pass for eighteen. You can’t very well lie about your height. Then I heard that musicians were needed to play for the soldiers, any age at all. I hotfooted it fifteen miles to the courthouse and took my place in line. The recruiter scowled when I reached the front. “You’re a knee baby yet,” he said. “Go on home.” I told him I meant to join the band. “And what would your instrument be?” he asked. My thinking hadn’t traveled that far. “The fife,” I spoke out. Which was a monstrous lie. He smiled at me and I felt limp with relief. Then he stood up and ambled out the door. Across from the courthouse a band had begun playing. We all heard the music stop of a sudden. A few minutes later the recruiter returned. He held out a fife. “Give us ‘Dixie,’” he said. I felt hot all over. Everyone waited. The fife seemed to burn and writhe in my hand like the Devil’s own tail. I heard Grandpap saying, as he had heaps of times, “A lie is a weed in the Lord’s flower garden.” Then that left my mind and I recollected him saying “Faith sows miracles.” I found what seemed to be the mouth hole. “‘Dixie,’” I announced. I closed my eyes. Then I commenced to blow and wag my fingers, singing out the song strong in my head. I believed it was coming from the fife as well, until I saw the faces around me. One man had his jacket over his head. The room echoed a considerable time after I’d finished playing. The recruiter’s eyes opened slow as a frog’s. I was surprised at his expression. “You’ve got spirit,” he said at last. “And boldness. And pluck enough, I judge, to practice almighty hard, starting today.” It was the first miracle I’d ever seen.

* * *

GIDEON ADAMS

* * *

The next day four of us marched to a recruiting tent to join the infantry. I happened to be the first in line. The enlisting officer had just asked me to sign when he noticed the hair curling out from my cap, saw for the first time that I was a Negro, and informed me in the most impolite terms that I could not be admitted as a soldier.

We left, despairing of ever fighting the South. Some of the men I knew put their pride in their pockets and joined as ditchdiggers. Some signed on as cooks or teamsters. Some stayed home, to hear once more that Negroes were cowardly, lazy, disloyal. I, however, refused to resign myself to serving with shovel or spoon. I would stand at the front of the fray, not the rear, and would hold a rifle in my hand. That recruiter had shown me the way.

I clipped my hair short that very night. The next day, I bought a bigger cap, one with a chin strap to hold it in place. Then I walked to a different recruiting station. The enlisting officer asked me my name. I foolishly feared he might recognize it. I looked up at a banner that read “One Thousand Able-Bodied Patriots Wanted,” and gave him “Able” in place of “Adams.” His brows furrowed at my fumbling reply. He asked me my age, then whether I’d any physical infirmities. He then asked what manner of service I intended. “Infantry soldier,” I firmly replied. Perhaps I’d spoken too firmly. He studied me. I wondered if my cap had slipped. He said I’d be paid thirteen dollars a month and that the regiment would serve ninety days, time enough to whip the Rebels three times over, he assured me. He put his finger on a line in his roll book. I nearly signed my real name, and clumsily corrected myself. I stared at the letters. I was no longer who I was. The recruiter told me to return the next morning. I left in a daze, glancing at the white men around me, who thought me one of them. The dread of discovery streaked through my veins. I gave my chin strap a tightening tug.

* * *

VIRGIL PEAVEY

* * *

By Jukes, wasn’t that a time! I walked forty miles with the rest of our company to catch the train to Montgomery. It was the first locomotive I’d ever seen. Didn’t she come charging into the station, snorting steam like a dragon! “Mind the undertow!” someone called out. “Don’t get sucked under!” I dashed away from the tracks for dear life. When I judged it safe, I scampered aboard, the whistle blew, and awa

y we went. My, but we ripped along like the wind! Most all the passengers were soldiers. Those in the boxcars broke holes in the sides with their guns to see where they were going. Men hung out windows and climbed on the roof, yelling and singing and drinking all the while. We all knew that the war was as good as won. Northern ribbon clerks would never fight. America had cut free from England, and now we’d cut free from the Yankee tyrants and would be independent forever after. A white-haired schoolmaster riding in the car heard our talk and shook his head. Every secessionist’s swaddling clothes are woven in Massachusetts, he said. His hobbyhorse is built of Maine cedar, his wedding ring worked by a Rhode Island goldsmith, his Colt revolver made in Connecticut, and his tombstone quarried in the hills of Vermont. There was silence. Then came a lively, democratic discussion, at the end of which we agreed not to throw him off the moving train, on account of his age, but to wait until we stopped at a station.

* * *

NATHANIEL EPP

* * *

I’m a dry-land sailor. Been from Maine to Mississippi. Horse, wagon, camera, and chemicals. I’d tie up, take portraits at twenty cents apiece, then move along down the road to fresh faces. In the spring of ’61 the birds were bound north, but I was steering south for Washington. Soldiers by the thousand were camped there, and every one of ’em wanted his picture made.

Joyful Noise

Joyful Noise The Half-a-Moon Inn

The Half-a-Moon Inn Rear-View Mirrors

Rear-View Mirrors Saturnalia

Saturnalia Zap

Zap Graven Images

Graven Images A Fate Totally Worse Than Death

A Fate Totally Worse Than Death Whirligig

Whirligig Bull Run

Bull Run