- Home

- Paul Fleischman

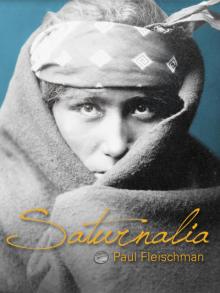

Saturnalia

Saturnalia Read online

Saturnalia

by Paul Fleischman

Copyright © 1990 by Paul Fleischman

First ebook copyright © 2014 by Blackstone Audio, Inc.

All Rights Reserved

Trade: 978-1-4821-0114-0

Library: 978-1-62460-621-2

For Ivy Ruckman

ONE

THE WEATHERVANES OF BOSTON were pointed north—the frigates, the angels, the cocks, the cows—and so, below, was Mr. Baggot. Marching down a dim alleyway, he raised his eyes from the shin-deep snow and gazed with envy at a rooftop rooster. The wooden bird was perched high enough to be sunning itself in the first light of day. While he himself, mused Mr. Baggot, trudged along in perpetual darkness, walking the lightless lanes of sin, rooting out evil and blasphemy. Such was the life of a tithingman.

It was December of 1681 and tombstone-cracking cold. Having bested fifty previous winters, Mr. Baggot was undeterred by the freezing gust of wind scouring his face and strode powerfully ahead without pause, parting the gale with his hatchet nose. In one hand he carried a well-worn copy of Spiritual Stepping-Stones for the Young, in the other he carried the symbol of his office, a walnut staff knobbed at one end and bearing a fox’s tail on the other. In fulfilling his duties at Sunday’s church service, he’d banged the staff’s knob on the doltish heads of a variety of squirming, whispering, laughing, face-making, Satan-claimed children, while waking no less than four dozing adults with a tickle of the foxtail. Following this, he’d used it to trip a pair of boys running from the meetinghouse, had reported two men for swearing and one for shamelessly splitting wood on the Sabbath, and yesterday, to his great disgust, had descended into the hellish waterfront taverns in search of disorderly patrons. How far this foul metropolis was from the paradise it had promised! A thought punctuated by the emptying, from above, of a chamber pot directly in his path.

He turned onto King Street and nearly collided with a scissors grinder pushing his wheel. Tinkers, broom makers, fishwives, and wood sellers all sent their cries toward the roof of Heaven. Horses, carts, and rumbling wagons shook the Devil from bed below. Mr. Baggot tramped on, his cloak flapping in the breeze so that he seemed to be constantly changing shape, as if made of black quicksilver. In the distance he glimpsed a pair of ships, sails full, leaving Boston harbor. Closer at hand, he spotted a shop sign in the shape of a book, and girded himself.

Like the town’s other tithingmen, he had spiritual charge of ten families, noting with care their attendance at services and testing their children’s knowledge of Scripture. Among the homes on his circuit, none distressed him like that of Charles Currie, printer, a man of great knowledge who seemed to prefer the companionship of his books on Sundays to that of his neighbors in church. And among the young under Mr. Currie’s roof, none irked him like William, the printer’s apprentice. Not because the boy failed to study, like most—but because he knew far too much.

Mr. Baggot entered the printer’s front room, causing the shop’s bell to tinkle softly. Waiting for his presence to be noted, he sniffed breakfast, heard talking farther within, glanced about at the books, papers, pins, and other sundries for sale, coughed conspicuously, took off his cloak, listened to an outburst of general merriment, and finally pounded his staff on the floor.

“Ah, good Mr. Baggot.” Mr. Currie’s round, reddish face appeared around a doorway. “You find us at breakfast. Will you take some bread and milk?”

“Bread and milk leave me hungry,” Mr. Baggot replied sternly. “Feeding the soul is my object. Your children’s ravenous ones, this morning.”

Mr. Currie smiled faintly. “Allow me a moment to instruct their souls to fetch bowl and spoon.” Turtlelike, he drew in his head, while Mr. Baggot wondered whether he’d been mocked. He felt his anger smoke, then ignite, ransacked his brains for some revenge on the man, and found himself staring at a calendar for December on the wall. His eyes traveled down to the twenty-fifth and narrowed. In the printer’s favor, Mr. Baggot had never known him—or any but a handful—to celebrate Christmas in any way, much less with the feasting, dicing, and drinking that marked that reeking day in England. However, the tithingman had heard tell that in this same month of the year Mr. Currie, out of his love for the ancient authors, imitated the Romans of old and observed a Saturnalia, a depraved, pagan festivity in which masters and servants traded places. Was this not far worse than Christmas reveling? The man, he noted, bore closer watching.

Mr. Currie returned, guided Mr. Baggot down a hall, past the printing room, into the house’s living quarters, and left him at a long bench near the hearth upon which perched six children of assorted heights.

“Now then.” Mr. Baggot removed the hat from his wispy, wind-tormented red hair and straightened himself to his full six feet. His staff in one hand, he opened his book with the other and paced before the bench.

“Sarah. Who was the oldest man?”

“Methuselah,” stated a confident voice.

“James. Who was the most patient man?”

“Job,” came the reply.

“Timothy. Who was the most hard-hearted man?”

“Judas,” lisped Mr. Currie’s youngest son.

The tithingman rapped his head with his staff. “Pharaoh!” he corrected. “As sure as you’re the most hard-headed boy in all Boston!”

Mr. Baggot paced, stopping before William, Mr. Gurrie’s fourteen-year-old apprentice. He was tall and thin as a spring shoot, growing up through and out of his black breeches and white shirt. The tithingman stared at him in silence. How very English he looks, he reflected. A wig on his head, stockings on his calves, pewter-buckled shoes on his feet. How avidly he reads. How well he speaks. How universally admired he is. And how black is his barbarous heart, he added. For beneath his linen shirt and his Latin, the viper wasn’t English. He was an Indian.

Mr. Baggot felt the boy’s mere presence blow upon his wrath like a bellows. He noticed an exhibition piece of his penmanship mounted on the wall and thought of his own two tiny grandsons. They’d been too young to hold a pen when they were slain in their beds by savages, just before the end of the Indian war that had brought William to Boston as a captive. The tithingman ground his yellowed teeth. What had inspired Mr. Currie to send the tawny to school, to hire tutors, to read to him from Homer and Plato until his learning surpassed Mr. Baggot’s own? No matter. Today he would humble the demon! He smiled knowingly, studied William’s eyes, then moved on without a question.

“Rachel. Describe your condition in Hell.” “I shall be dreadfully tormented,” came the memorized answer.

“Ruth. What company will you have there?”

“Legions of devils and multitudes of sinners.”

“Timothy. Will company afford you comfort?”

“It will not,” Mr. Currie’s son lisped, “but...”

He halted. His clasped hands gripped each other. “But will surely . . .” His eyes appealed to

the ceiling.

“But will surely increase your woes!” the tithing-man finished the sentence for him, and increased the boy’s present store of woes by the amount of two sharp raps on the head.

There followed several more minutes of drilling, Mr. Baggot passing over William each time. He next asked to examine the older children’s notes taken on Sunday’s sermon, and was saddened to see that the three-hour oration had left so little trace in their notebooks. He then offered them his weekly exhortations: to pray alone in secret places, to pray unceasingly, even during sleep, to rip sin from their souls, root and stalk. He walked toward the door with his book and staff, then turned.

“One question more.”

He stared at William and h

alf believed he’d fixed his gaze on the black eyes and bronze skin

of his grandchildren’s murderer.

“Do you think it just that one of you has answered no questions this morning?” he asked.

At once, William spied the man’s scheme. “Grievously unjust!” he declared. “Put me any question you choose!” He wouldn’t let the tithingman turn the others against him.

“Grievously unjust, indeed.” Mr. Baggot searched hopefully for signs of resentment toward the apprentice.

“Though why should we fret if he’s been favored?” spoke up Sarah, the printer’s eldest daughter. “Is that not just what Jesus taught in the story of the laborers in the vineyard?”

William smiled discreetly at this brilliant outflanking maneuver.

“Matthew, chapter twenty,” added one of Mr. Currie’s sons.

“Silence!” Mr. Baggot glared at his students. The whole lot were bound for Hell as it was— so why did he toil on their blighted behalfs? “William desires a question. He shall have one!” Slowly, he approached the apprentice. “A simple question, concerning his ancestors.” He adjusted, then tightened, his grip on his staff.

“On a pole in Plymouth sits the head of the Indian Philip, the tawnies’ blood-thirsting general. The Israelites too were assailed by godless tribes. When they fought against the Midianites, the heads of two of the enemy’s princes were paraded as a sign of victory.” Mr. Baggot paused, his eyes twinkling gaily. “I ask for but one of the princes’ names.”

His audience viewed him in disbelief. The Bible was as full of such names as the ocean was of fish.

“This question is not from our book,” said William.

Mr. Baggot tucked Spiritual Stepping-Stones for the Young into a pocket and grinned. “‘Any question you choose’ was your request.” At last, the dark-skinned scholar had stumbled! The tithingman readied himself to leave a dent in his head to mark his triumph by.

“Not from our book,” William continued, head lowered, “but from the book of Judges.” Eyes closed, he reached back in his memory. “Chapter seven.” Mr. Baggot’s own pair opened wide in alarm.

“‘And they took two princes of the Midianites....’” The apprentice raised his head. His eyelids lifted as if he were waking from a trance. “Oreb,” he answered the tithingman.

Mr. Baggot’s teeth scraped. His breathing became heavy. His skin tightened over his bony face as if drawn taut with a winch. Strangling the heavy staff in his hand, he leveled a murderous stare at William.

“’Tis in my power to have you whipped at the public post,” he stated softly, his body shaking from the effort of restraint. “Or to set you in the stocks or pillory. To have your ears lopped off, tongue bored with a burning awl, or your forehead branded. All I need do is find your foot a hair past the bounds of the laws of the town.” He bent forward until their noses nearly touched. “And I want you to know that my eye is upon you. Like a spider’s eye upon the fly.” His voice had narrowed to a whisper. “And that one day soon—I’ll snare you.”

He straightened, turned, and strode out of the room. By ear, William followed his rapid progress through the rest of the house, decided against shouting the name of the other prince of the Midianites, and heard the front door slam.

All six children were set in motion by the sound: toward school, the outhouse, the pump, the spinning wheel.

“Keep your eyes skinned for him,” counseled Sarah.

William smiled. He entered the printing room, rubbed his hands against the cold, picked up his wooden composing stick, and began setting type as if nothing had happened. And what had? Mr. Baggot had asked him a question; he’d answered it, correctly. Was it sinful to remember well? His memory had always been strong, though in truth his focusing it on the Bible was closer to sport than worshipful study. He’d been born into the Narraganset tribe and disliked the Englishmen’s heartless Jehovah. But he enjoyed demonstrating to Mr. Baggot that all Indians weren’t witless, and took pleasure in turning the book’s own words on the tithingman and others found to be flouting Christ’s message of love and compassion.

Nimbly, he picked letters from the type-case, setting them side by side in his stick, then glanced at the title of the sermon he was setting: “He That Knows and Does Not His Master’s Will Shall Be Beaten With Many Blows.” He thought of Mr. Baggot’s threatened punishments. Had a more brutal race of men than these Christians ever roamed the earth? How else but through their ruthlessness had he come to wake up in Boston this morning? He looked out at the snow and realized that it was now exactly six years back to the December evening the English had attacked, slaying all before them, young and old, women as well as men, like their Lord’s avenging angels. And avenging what? It was Philip and his Wampanoags the English were at war with. Merely out of the fear that the Narragansets might join Philip’s side, they’d been slaughtered by the hundreds that night. Discovering that his fingers had stopped working, the apprentice roused himself, strove to evict that topic from his thoughts, and reached quickly for an “i,” an “n,” a “g,” and then a period.

“How comes the sermon, William?” Mr. Currie, a heavy log under each arm, entered the room and dropped the wood with a crash on the fire dozing in the hearth, provoking a tirade of snapping and sparking.

“I’ve come to the torments in Hell awaiting unruly servants,” he replied. “Fetching hot coals with their bare hands. Polishing Satan’s throne without end.”

Mr. Currie sighed. “I suspect the author, Reverend Peck, is vexed with his serving girl again.” He prodded the fire with an iron poker as if it were a balky cow. “Though ’tis certain you won’t slave in Hades beside her. I’ve never had an apprentice so quick-fingered with type.”

William smiled inside. Like a frog’s tongue, his right hand shot out and snapped up a capital “h,” then an “e,” then a pair of “l”’s. Mr. Currie, meanwhile, took out a stone bowl and commenced mixing ink from lampblack and oil.

“Are we sailing for Troy tonight?” asked the printer. By which means he’d inquired for the past several weeks whether William had studied three more pages of the Iliad, which the two of them and Sarah were reading together in Greek.

“Ready to raise anchor,” came William’s ritual reply.

Mr. Currie nodded. Gwenne, the family’s nineteen-year-old serving girl, began sweeping out the weeks-old, dirtied sand that protected the wooden floor.

“Have you spied the lump Mr. Baggot gave young Timothy?” she addressed the room.

Mr. Currie looked up and shook his head, fixed two pages of type in the press, and spread some ink on a marble slab.

“In faith, I ought to have swept the man out the door with the other leavings,” she declared. She wielded her birch broom ferociously and gradually followed it out of the room. A minute later she returned, sowing handfuls of fresh white sand from a bucket. “’Twould be joy to give him such a knock with his staff!”

“Soft now, Gwenne,” cautioned Mrs. Currie. A smiling woman, whose fingernails were as likely to hold ink as her husband’s, she led her young son James into the room, lifted him onto a box so that his eyes just cleared the top of a typecase, and continued her lesson on which letter was to be found in which compartment. A moment later, Amos, the printer’s brawny journeyman, strode inside, called out “Good day,” and received five different-pitched echoes in reply. Warming his hands, he watched Mr. Currie tug on the press’s long iron handle. “What are we pulling the Devil’s tail for today?”

The press’s timbers groaned, and inked type met dampened Dutch paper. “A tract on profane and promiscuous dancing.” Mr. Currie carefully searched the page he’d printed for signs of damaged type. “Written by a deacon in Deerfield. He’s against it.”

William began setting the last page of his sermon, wherein lazy, insolent serving girls were pictured soot-blackened and sobbing, ceaselessly cleaning the myriad chim

neys of Hell. Knowing where to find each letter without looking, he was able to keep watch on the world out the window and found himself smiling, given the text he was setting, at the sight of Mr. Hogwood and Malcolm, his manservant, trudging toward him up King Street. He watched them traverse a drift, the squat master’s short legs nearly lost in the snow, while his long-legged servant traveled with ease. The pair crossed the road, stepping over the open sewer running down the middle, then skirted a trio of scavenging pigs. Mr. Hogwood’s plump face and Malcolm’s wedge-thin one passed like visions before William’s window, following which the front bell tinkled, the apprentice left his place at the typecase, and found the two fully fleshed in the shop.

“A quire of Holland paper,” Malcolm commanded importantly.

William departed the room to fetch it, leaving Mr. Hogwood to inspect the quill pens and his servant to put the time to profit by nodding, then grinning, then lifting his hat to a female passing by the front window.

William returned. Malcolm whirled from the window. “And a pair of quills!” he ordered, unaware that Mr. Hogwood had set two on the counter. The manservant paid for the purchases, placed them with the others in his basket, and ceremoniously opened the door for his master, trailing him down the street, as instructed, at a distance of two paces.

Left to his thoughts, Malcolm contemplated the physique of an approaching milkmaid, while Mr. Hogwood, barber and wigmaker, wondered at Mr. Currie’s neglect of his appearance. The man was a printer, a position of respect, yet he paid no mind at all to his wig. It was shabby and hadn’t been dressed in months, as was true as well of those to be found on his sons, apprentice, and journeyman. He surveyed the male heads in view, all of them properly wigged and hatted. What would become of the world if a man’s attire no longer declared his station? The lion ruled over the fox, who was lord to the mouse; so it was as well among men. For which cause wigs were sold in a score of styles, each assigned to its own rank of wearers, that a magistrate might be known at once by his magnificent, perfumed cascade of curls, made from the finest human locks, while an oyster peddler’s head might hold only a grimy scrap of horsehair. Though neither rich nor powerful, Mr. Hogwood, as upholder of this hierarchy, felt raised up within it and had adorned himself in the silk waistcoat, gold buttons, silver lace, and flowing wig of his betters, despite the fact that it was against the law to dress above one’s station. Undeceived by his resplendent appearance, a mangy dog approached the wigmaker and sniffed at his calf with outrageous familiarity.

Joyful Noise

Joyful Noise The Half-a-Moon Inn

The Half-a-Moon Inn Rear-View Mirrors

Rear-View Mirrors Saturnalia

Saturnalia Zap

Zap Graven Images

Graven Images A Fate Totally Worse Than Death

A Fate Totally Worse Than Death Whirligig

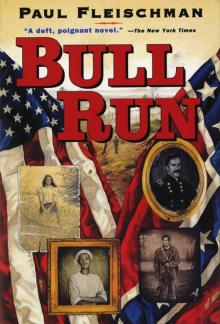

Whirligig Bull Run

Bull Run