- Home

- Paul Fleischman

Whirligig

Whirligig Read online

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the author’s copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

Contents

Title Page

Copyright Notice

Dedication

Party Time

Weeksboro, Maine

The Afterlife

Miami, Florida

Twinkle Twinkle Little Star

Bellevue, Washington

Apprentices

San Diego, California

“Everybody Swing!”

Copyright

For Honey and for Pearl

Party Time

Brent turned toward his clock. It was five thirty-five. He hated the hours before a party. A nervous energy whipped back and forth inside him. He focused again on the computer’s screen and careened through the video game’s dark passages, firing at everything speeding toward him, borne along by the never-ending music.

“Brent!”

His mother’s voice echoed up the stairs. Brent paused the game. The firing and explosions ceased as if a window had been closed on a war.

“Dinner!”

“All right.”

He played on, chewing up the minutes that stretched before seven o’clock. Why couldn’t you fast-forward through time the way you could with a video? He flicked another glance at the clock. Five forty-one. Real time was a drag.

He went downstairs. His parents had started eating. When they’d moved to Chicago a few months before, they’d suddenly begun dining in the kitchen, where they’d put a small TV. Brent served himself at the counter, then took his stool at the island and watched with his parents.

The Friday sports news was on, annotated by his father’s grunts and snorts. Brent had learned to judge his mood from these. He reconnoitered his father’s long, handsome face and studied the wrinkles, fine as if scratched in with a burin, feeding into his eyes. The promotion within his car-rental company had rescued them from Atlanta’s heat, put Brent into a private school, bankrolled Brent’s mother’s furniture-buying spree, but hadn’t seemed to improve his own spirits. The caustic complaints about work had begun again. Lately, Brent had begun to feel sorry for him.

The news ended. His father reached for the remote, which Brent’s mother always put to the right of his fork when setting their places. He dodged commercials, serving the rest of the family a finely ground visual hash. Switching the control to his left hand so as to take a bite, he inopportunely dropped it when the screen showed the victims of an African famine. A child crawling with flies was wailing. Brent’s father scrambled for the remote. A white woman now faced the camera. “This tragedy—” she began, then was cut off.

“Let’s go there for our next vacation,” said Brent’s mother. The remark drew no comment.

“I’m going to a party tonight,” Brent spoke up.

His father dismissed from the screen a male newscaster, then a woman selling detergent. Brent found himself thinking of his parents’ former spouses.

“I wish I was,” said his mother.

All three watched a commercial for the new Jaguar.

“What do you say, Brent?” said his father. “Nice lines, huh?”

“Very nice,” Brent replied.

He examined his father’s words for signs that a Jaguar might now be in reach with his new salary. He imagined himself driving it, observed by the assembled student body, adding to the daydream a Calvin Klein shirt from the advertisement that followed. He put his dishes in the sink.

“Write down where you’ll be,” said his mother.

He skipped upstairs and showered, scrubbing himself with medical thoroughness. Though he was in his junior year, he still only had whiskers on his upper lip and chin. He shaved his whole face anyway, then applied aftershave. He put on deodorant and gargled with mouthwash. Taking his comb, he parted his straight blond hair down the middle, confronted the mirror, then combed it straight back, like the models in GQ. He worked in the mousse, imagining the hands raking his hair were Brianna’s. Next he inspected his left ear’s gold earring. At his school in Atlanta, it had been the right ear. Likewise in Connecticut. But at the Montfort School, in the western suburbs of Chicago, it was the left. His father’s corporate climb had demanded four moves in the past seven years. Earrings were one of the first things Brent checked.

He returned to his room and flipped on the radio. Discerning what stations were considered cool was another of his moving-in tasks. No spell-chanting shaman knew better the importance of precise adherence to tradition. And keeping the right music flowing, using headphones between house and car, was as vital as maintaining a sacred flame. With the room now prepared, Brent set about dressing. It was May and no longer rib-rattling cold. He considered his large collection of T-shirts, weighing their logos, color, and condition. To impress without risking being made fun of was his mission, the latter especially important in the case of a party at Chaz’s. Especially when you hadn’t actually been invited.

He chose khakis and his Chicago Bulls T-shirt. He attached his wallet chain to a belt loop, tucked the wallet in his back pocket, then couldn’t decide whether or not to wear his Vuarnet sunglasses. He finally stuck them in his shirt pocket as a compromise, then looked at the clock. It was six-thirty—still too early to leave. For half an hour he played video games, losing all of his lives in short order, the radio booming over the games’ noise, his mind elsewhere. At seven he took off.

He drove to Jonathan’s and honked. His friend bounded out, lanky and loose-jointed as a clown, wearing a Cubs cap backward and a pair of shredded jeans. Instantly, Brent regretted the choice of his neatly ironed khakis. They drove off.

“So how come you need a ride?” Brent asked.

“Forgot to pay my car insurance,” said Jonathan. “My dad took the car for a month. ‘There are consequences for our acts, my boy.’ Like having to show up in your Studebaker instead of my Mazda MX-6.”

“It’s a Chevy, not a Studebaker.”

Jonathan winced wearily. “No kidding.”

A sense of humor was a luxury that Brent had never been able to afford. He was always the new kid, stumbling through the maze, never quite rich or good-looking or athletic enough to join the elite. Unless he played his cards right at the party tonight.

“So how do you get there?”

“Get on 355,” said Jonathan. “I’ll show you.”

Brent drove through Glen Ellyn’s maple-lined streets. Chaz lived all the way across the city, in Wilmette, on the lake. Montfort drew from all of Chicago. It was Brent’s first private school. He’d cheered when he’d heard that his father would be making enough money to afford the tuition. Then, when they’d moved from Atlanta in March, he’d found that, measured against his new peers, he was suddenly a lot poorer than before. Getting any respect at Montfort was going to be like climbing a glass mountain.

“Get on the East-West Tollway,” said Jonathan. The new song by Rat Trap was on the radio. He turned it up until the dashboard vibrated. “Then we’ll take the Tri-State north. Then we’ll cut over. I’ll tell you where.”

“And you’re sure it’s okay, me coming?”

“Trust me! I’m his friend. You’re my friend. Therefore, you and Chaz are friends. As was proven by theorem 50 in chapter 6. Stop worrying! It’s party time!”

Jumping from one freeway to another, they zigzagged across Chicago. Brent had his doubts about Jonathan’s logic. But at least he was certain Brianna would be there. This was a chance to be with her without risking actually asking her out, to be seen with her, to make a statement. To

take the next step. Maybe more than one.

They found the house, clustered with cars as if it were a magnet. Cherokee, Honda, BMW, another Cherokee. Brent knew all their models and prices. Judging by the crowd, he figured they were on the late side, which was fine. It gave the impression he had other, more important things on his schedule.

He parked and put on his headphones. They approached the stone house. It was vast and turreted, looming above them like a castle. Brent reached for the knocker, but Jonathan opened the door as if it were his own.

“Hey, it’s a party. Remember?”

Inside, the rooms seemed too large, the ceilings too high. Brent felt out of scale. No one seemed to be around. He trailed Jonathan through the labyrinth, at last emerging onto the back patio. Music was booming from a sound system to their right. Below them, in the tennis court and on the grass and inside the gazebo, lounged the cream of the junior class. Brent felt he’d gained a glimpse of Olympus.

It was dusk. They wandered toward the others. Then Brent noticed something. He grabbed his friend’s arm.

“Is there a dress code or something?”

Jonathan stopped. Then he saw it too. Everybody was wearing either all white or all black.

“Jesus!” Jonathan smacked his head, then grinned. “Forgot again.”

“Forgot what?” Brent knew the panic had shown in his voice.

“We were supposed to wear white or black, like chess pieces. Chaz has some big party game dreamed up.”

Brent glared at his friend. He felt he’d been tricked. Fury rose up in him from a deep well. He’d been a head-banger as a toddler and still threw tantrums when he didn’t get his way. He knew he couldn’t afford a tirade here. He pulled off his headphones and tried to form his reply.

“Relax,” said Jonathan. “Chaz always has a theme. Check out the tennis court. It’s a big chessboard. Must have used chalk. He loves this kind of thing. He’s in Drama Club. Figures.” He eyed Brent. “Don’t sweat it.”

He moved on, robbing Brent of his lines. Without Jonathan next to him, Brent felt conspicuous. Everything about the party made him nervous. Then the thought hit him that he could leave. He stuck out enough already without the added business of the clothes. This was the time, before the party game started, whatever it was. Down on the tennis court, two figures in white were rollerblading. He debated, teetered toward flight, started to leave—then sighted Brianna. The balance swung. He trotted and caught up with Jonathan, walking beside him as if nothing had happened. Then each felt a hand on his shoulder. It was Chaz.

“A yellow shirt and blue jeans?” he inquired. He affected the headmaster’s English accent, sternly surveying Jonathan. He was tall and long-jawed, his sandy curls topped by a gold crown. “Really, Mr. Kovitz. This will lower your grade. Learning to follow directions is vital both to your success at Montfort and in the wider world beyond. Regardless of what pathetic, godforsaken piece of it you occupy.”

Jonathan smirked. “I thought school was over.” He viewed Chaz’s crown and fingered his black cape. “Not to mention the Middle Ages. Anyway, I don’t have a car at the moment, so Brent here drove me. I figured you could use an extra pawn or two.”

Chaz took stock of Brent’s catsup-red Bulls shirt. “Points off,” he said. He dropped the accent. “Brent Bishop, right?”

Brent nodded his head.

“Bishop, like the chess piece,” Chaz mused. “Let’s see if he moves back and forth diagonally, the way a bishop should.”

He stood behind Brent, put both hands on his shoulders, and guided him toward the left. Brent resisted at first, them complied, allowing himself to be treated like a toy, hating his helplessness. Abruptly, Chaz reversed direction, pulling Brent stumbling backward.

“Works fine to the left. Let’s try the right.”

People were watching. Brent felt like slugging Chaz, but knew his tormentor was taller, more muscled, and the de facto ruler of their class besides. If Chaz said that easy-listening music was hip, then it was. Losing his cool here would be suicide.

“Seems to be in good working order,” said Chaz. He stopped, then turned Brent to the left. “Bishop to drinks table,” he called out in chess-move fashion. Struggling not to trip, Brent was marched across the grass, through a circle of girls, and up to the table. He felt Chaz’s hands release him and prayed his host would vanish. He did.

He replaced his headphones to help shut out the scene and stood staring, dazed, at the bottles before him. He felt as if he were still onstage. Playing to his audience and his own need, he poured himself a scotch and soda, heavy on the former. He added ice and sipped it quickly, feeling it run through him like a river of lava. Discreetly, he scouted the territory. The smell of pot smoke reached his nostrils. He spotted Jonathan in a group of boys on the lawn and headed that way.

The talk was of the Cubs. Brent marveled that people could publicly root for such perennial losers. The Bulls in basketball were different. They won. Both he and his father had bought Bulls shirts their first week in Chicago. His own stood out less among the whites and blacks as darkness fell. Then lights came on above the tennis court and inside the gazebo.

“The human chess game will commence in thirty minutes!” Chaz announced from the patio.

“Should be interesting,” said the boy next to Brent.

The subject switched to hockey. Brent pretended to listen, sipping his drink and watching Brianna. He wanted to catch her alone. At the moment, she was talking with two other girls. She was drinking a beer and had a sullen look, her wavy blond hair reaching down her black dress like a hanging garden. His knowledge of her was sketchy. In his two months at Montfort he’d learned that she’d recently broken up with someone, that she stood near the top of the pecking order, and that her father, rumor had it, was worth a hundred million. He also knew, for a fact, that she was gorgeous. Having her for a girlfriend would mean instant respect. And why shouldn’t she like him? He was tall, a little skinny perhaps, a bit uncoordinated, but reasonably handsome, with a square chin and no braces or acne. She was probably sick of the same old faces. She’d smiled at him off and on when they passed. They’d been assigned to the same group project in history. Making use of his newcomer status, he’d often asked her questions about Chicago, offering in return his services in math, his best subject. She hadn’t taken him up on it as yet, but finals were coming. He had hopes.

He made another drink and returned, his nerves pleasantly numbed by the scotch. He took off his headphones. He was feeling more comfortable, proud of the fact that he could hold hard liquor. On the patio, Chaz had taken off the rap and put on French-sounding accordion music. It was so corny it was cool, and somehow fit the moment: a spring evening, the air warm at last, the leaves thrusting from the trees again and crowding out the sky. A faint breeze stirred the greenery.

Around Brent, the talk turned to cars, then gradually focused on Porsches. He heard his cue and roused himself.

“The 4-S really flies,” he volunteered. “But tons of repairs. Always in the shop. Don’t even say the word Porsche to my dad.”

“He drives one?” asked Jonathan. “I always see him in that Continental.”

“Back in Atlanta,” said Brent. “Finally sold it.” It was the sort of lie that would never be found out, the sort he’d drawn on often. Moving had at least that one advantage. Over the years, he’d grown adept at creating alternate pasts for himself. He glanced to his right and was returned to the present. Brianna was crossing the grass, alone.

He slipped from his group and hurried his steps to intercept her.

“Hi,” he said.

She looked startled. She hadn’t seen him in the shadows. “Hi,” she replied flatly, then moved on.

He strode beside her briskly to keep up. “So who are you in the chess game?”

She reached the drinks table and poured herself some vodka. “Beats me.”

She added tonic to her cup. He added scotch to his and sipped it. He lifted the top off the ic

e bucket for her. She ignored the gesture and walked away. He followed, emboldened by the alcohol to try to overcome her coolness.

“That history test was deadly,” he offered.

“Sure was.”

He tried to fight through the accordion music and the fog in his brain to find something to say, unaware she was headed for the crowded gazebo. He sipped his drink.

“If you need any help in math—”

Brianna stopped short, squeezed her eyes shut, then wheeled and screamed, “Stop hanging all over me!”

They were well lit by the light in the gazebo, where Chaz was giving a waltzing lesson. All heads turned toward Brianna and Brent. Conversation stopped.

“You’re like a leech or something! Get off of me! Can’t you take a hint? Go bother someone else! And that goes for at school too!”

There was silence but for the accordion’s cheery tune. Brianna stormed up the gazebo’s steps and disappeared into the crowd.

Brent stood, brain and limbs paralyzed, as if turned to stone by her curse. He’d never been in such a situation and had no ready response. The music and the black and white figures facing him made him wonder if he was dreaming.

“Been rehearsing that scene long?” asked Chaz for all to hear. “Drama Club needs you.”

There was laughter at this. Brent’s thoughts tilted crazily. He pictured them all repeating the scene to their friends, replaying it like the sports highlights, guffawing over it at the twenty-year reunion. He turned, desperate to get out of the light’s glare, and started toward the shadows. Bounding down the steps, Chaz cut him off and placed both hands on his shoulders.

“Bishop to penalty bench,” he called loudly. “Ten minutes, for sexual harassment.”

More laughs. He aimed Brent toward a stone bench. The hated grip on his shoulders again, the public humiliation, the snickers, the alcohol, all mixed and detonated inside Brent. He stopped, whirled, throwing off Chaz’s hands, and swung with all his might.

“Jesus!” came from the gazebo.

The blow missed Chaz’s face, scraping his ear. Both he and Brent stood in shock, caught off guard, breathless. Chaz’s crown had fallen off. Brent aimed a ferocious kick at it, connected, sent it spinning over the grass, then turned and stumbled toward the patio, alone.

Joyful Noise

Joyful Noise The Half-a-Moon Inn

The Half-a-Moon Inn Rear-View Mirrors

Rear-View Mirrors Saturnalia

Saturnalia Zap

Zap Graven Images

Graven Images A Fate Totally Worse Than Death

A Fate Totally Worse Than Death Whirligig

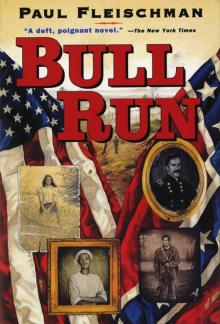

Whirligig Bull Run

Bull Run