- Home

- Paul Fleischman

The Half-a-Moon Inn

The Half-a-Moon Inn Read online

Contents

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Excerpt from Seedfolks

About the Author

Also by Paul Fleischman

Credits

Copyright

About the Publisher

1

Aaron awoke to the sharp cry of sea gulls, suddenly remembered what day it was and burst out of bed as though the sheets were afire. He could hear that his mother was already up, hitching the horse to the wagon. He scrambled into his clothes, scooped up an armload of woolen cloth and shot out the door—for today they’d be traveling to Craftsbury!

“Whoever you are behind all that wool—good morning to you!” called his mother. Aaron smiled and scurried by her, his arms piled high with the wool she’d washed and dyed and spun and woven into cloth. He felt as restless as a chipmunk on the first day of spring, for it was but once every month that they left the seacoast behind them and wound their way through the forest to Craftsbury, where all the world seemed to gather on market day.

There’d be farmers and fortune-tellers, chandlers and capmakers, all shouting their wares at once. The smell of roasting chestnuts would drift through the air, above squealing pigs and bleating lambs and crowds of people swarming about. It was there that Aaron and his mother would sell their cloth, returning home the next morning with oats and lamp oil and more raw wool, to be dyed the colors of the ocean deeps and woven into cloth textured like the sea itself.

“There’s breakfast a-waiting for you,” called his mother, “if you can stay put in one place so’s to eat it.” Aaron darted in and out of the one-room house, fit the last load of cloth in the wagon and glanced out at the sea. The waters were still and speckled gold with the sun, and though the early November air was chilly, there wasn’t a cloud to be seen in the heavens. A fine day indeed for a journey.

He dashed back inside and sat down to a bowlful of barley gruel. Then he pulled a stub of chalk from his pocket, took up his slate and wrote: “Couldn’t we leave now and eat later?” For Aaron had been born unable to speak.

“Well now, I’ve my own question to ask of you first, my dove. Don’t you come due for a birthday tomorrow?”

Aaron nodded his head.

“And won’t you thereby arrive at a full twelve years of age?”

He nodded again.

His mother put down her spoon, and ran her fingers through her long brown hair.

“You see, my dove, I’ve been thinking.” Her voice was hesitant, her eyes scanning him. “And I believe it’s come time for me to let you learn to pull your own oars and steer your own rudder, like other boys of your age. And so I want to ask you, Aaron, if you’d be a-willing to do something even more adventuresome than traveling to Craftsbury.”

Aaron looked puzzled. “What?” he wrote on his slate.

“I want you to stay here while I’m gone.”

A chill darted up his spine.

“Alone?” he wrote.

“Yes, alone.”

Aaron gazed at his mother. Never before had he been out of her sight for more than a few hours, much less overnight. With his father lost at sea, there’d been no one but his mother to raise him. And though she’d taught him to read and write as soon as he was able, she’d still feared to let him stray out into the world alone, afraid that he’d stumble into danger without a voice to call for help, or that he’d be mocked for his muteness or even stoned to death as being devil-possessed. Aaron had always been accustomed to having her near, and like the ocean itself, her presence was woven into the background of all of his memories. Yet he knew what she expected of him, and though a nervous dread tugged against him like an outgoing tide, he picked up the chalk, and wrote: “I’ll stay.”

A smile rose into her eyes. “I’m proud of you, my dove.”

But Aaron was too full of apprehensions to feel warmed by her pride. What if something went wrong—if the house caught fire or was struck by lightning or the waves washed in from the sea? Suddenly he thought of changing his mind and going along with her after all, imagining himself up on the wagon where he always sat, sailing grandly through the forest, with the morning air sharp and the birds flitting gaily about the trees—then he awoke from the vision, knowing that it wasn’t to be.

His mother finished her barley and rose up from the table. “You’ll do fine, my dove,” she said to him.

She moved about the room, filling a basket with food for the journey. “I’ll put up overnight at The Peacock’s Tail, and be home noon tomorrow, just as always. And not one moment later.”

She stopped what she was doing and looked into Aaron’s face. “There’s just one thing you’ll have to remember, my dove—and that’s never to leave sight of the house. For there’s no town to be reached but by traveling inland, where the roads wriggle about the forest like a family of snakes, broad and fine as the king’s highway one minute and dwindling down to rabbit runs the next. Always keep close to the sound of the waves, for the woods are full of wolf packs and bears, and a-crawling with brigands like a corpse full of maggots.”

A shiver swept through Aaron as he recalled how only last month on the journey to Craftsbury they’d passed Lord Tom himself, the most notorious highwayman of all Bingham Woods. He was raging in a fury, with his huge arms bound with chains and his great red beard flying madly in the wind, having been captured at last and being escorted to prison to be hanged once and for all. Aaron shuddered at the memory of his snarling face, with his one blue eye and his other brown, and Aaron tried to shake off the sight of the man as he got up from the table, picked up his mother’s basket of food and accompanied her out to the wagon.

“There’s oil in the lamps and food in the cupboard and no need to worry, my dove.”

Aaron gazed up the road, following it through the dry, brown fields and into Bingham Woods in the distance. His mother kissed him on the cheek and climbed onto the wagon. Handing the basket of food up to her, Aaron felt lonely and abandoned, longing to be up on the wagon as she was, going where she was going.

“There’s only one thing that’ll be out of the ordinary,” she said. “I’ll be a-bringing you back a certain something for your birthday, something befitting such a hardy young man.”

Aaron tried to look cheered.

His mother smiled down at him. “Good-bye, Aaron.”

He waved good-bye.

“I’m proud of you, lad,” said his mother, and she flicked the reins and headed off toward the trees.

2

Long after the wagon had disappeared into the woods, Aaron remained standing where he was, staring off in its direction, following along with his eyes where he imagined it to be. Sea gulls circled and squawked overhead. A breeze blew through his hair, and at last he turned back toward the house and lay down in the grass, gazing out at sea.

After all, it was only half a day’s journey to Craftsbury, he said to himself. She’d be back soon enough—why, tomorrow at noon, and not one moment later. He’d begun to feel better already. And there’d be a birthday present coming home with her as well! He broke into a smile, feverishly wondering what it might be. His mind was aflutter with visions as he lay there, listening to the gulls and feeling the sea breeze on his face, when he suddenly realized he was all on his own—and free to do whatever he wished. He felt airy and light and bursting with energy, and he began rolling in the grass, dizzily, joyfully, squealing with laughter inside. Staying home all alone would be grand!

He picked himself up and scampered down to the beach. Immediately he remembered what his mothe

r had told him, and he looked back at the house, perched just beyond the grasp of the tides. His father had loved the solitude of the sea, and he’d cleared the road that led down from the forest by himself and built a house at its end. Small and white with a thick thatched roof, it was stuck out on a point jutting into the ocean, where there were no other houses about, and under its gaze Aaron gleefully passed the morning.

He skipped stone after stone on the water. He scrambled about the rocks like a crab. He imagined himself a mighty orator, addressing the waters in a thundering bass, commanding the very ocean as though he were its captain.

“Break now, waves, and split your ribs on the rocks! Let the spray fly up, let the waters foam! Fishes—swim! Snails—crawl! Sea gulls—dive for your dinners in the sea!” He could hear himself clearly inside his head, shouting out his orders in a fine, deep voice, trilling his r’s magnificently, casting his words out over the water, all the way to the horizon.

When he grew hungry, Aaron walked back to the house and kindled a fire in the stove. He cooked himself a bowl of buckwheat groats and returned once again to the beach, peering into tide pools and scanning the horizon, imagining himself a sailing man like his father. All afternoon he busied himself, and when the sun at last edged back behind the trees and shadows spread onto the beach, Aaron reluctantly walked back home, hungry and tired and with his pockets full of shells.

It was growing dark in the house, and he lit one of the lamps, built a fire in the stove and placed a pot of peas on to boil. Night was coming on and the breeze picking up, with a few ragged clouds blowing in from the sea. He listened to the wind as it rushed over the house, rattling the windows and fluttering the flame in the lamp, and felt a chill pass through him.

Swiftly the light left the sky. Outside, the waves crashed blindly against the rocks in the blackness, and suddenly the house seemed empty and abandoned, as though its last owners had long since left it to the spiders and swallows. Aaron gazed slowly about the room, at the spinning wheel, at the clock his father had brought back from his travels, at the massive loom, still and silent in the corner. The house felt as lifeless as a tomb, and he longed to hear the sound of his mother spinning, or of her softly singing while she wove.

Aaron pulled his chair up next to the stove, his eyes alert and his ears tensed to every sound in the wind, suddenly believing himself to hear footsteps approaching, then distant thunder, then the clatter of horses’ hooves. He stared at the wall across the room, and seemed to see it almost imperceptibly bulge and sink, like skin over a heart. The wind roared over the house in a rage when he rose to fetch himself a bowl of porridge, and he ate as quickly and quietly as he could, trying to keep from looking out the windows, for fear of what he might see.

When he was through with his dinner Aaron sat for a while, letting the fire burn down. Then he latched the door, blew out the lamp and climbed quickly into bed. He lay there listening to the wind whistling by on the other side of the wall, glanced out the window across the room and beheld an entire armada of clouds, silently riding the wind in from the sea. He watched them passing before the stars, as stealthily as spies, gazed at them endlessly migrating across the sky and slowly fell into sleep.

When he awoke in the morning, Aaron sensed a chill in the air. He looked out the window, dashed out of bed and threw open the door in disbelief. Snow was falling thickly out of the sky.

He darted back across the room and jumped into his clothes, shivering in the cold and with his teeth chattering at a gallop. Never had he known the first snow of the winter to arrive so early. Usually it didn’t come until Christmas—and then only a dusting of snowflakes at that. But this!

Aaron squeezed into his boots and ventured outside, to find his feet sinking into a full half foot of snow. The fields were covered completely, and the woods in the distance were white. It must have been snowing all night.

He looked about in amazement, walked back inside and lit a fire in the stove. What would become of his mother? A half foot of snow wouldn’t hold up the wagon, and she’d said she’d return home by noon, just as always. He peered out the window at the road, but could barely make it out under the snow. Surely she wouldn’t leave him here longer than she’d promised—not on his birthday.

Aaron shed his coat and his cap and sat down by the stove. The wind had died down during the night and there wasn’t a sound to be heard from outside save the movement of the waters and the brush of snow against the windows. Hour after hour he waited, keeping watch on the road that led from the forest, gazing at the snow drifting down.

He glanced at the clock. The hands said noon. He walked outside and stood peering up the road, but his mother was nowhere in sight.

He tramped back inside and put more wood on the fire. Where could she be? He heated the porridge he’d cooked the night before, but found he wasn’t hungry. He decided to whittle a piece of driftwood, but couldn’t stop his eyes from wandering to the window, and he put his knife away.

All afternoon he waited, keeping his eyes away from the clock, staring out the window in expectation. Snow continued falling without end, and slowly the light departed from the sky. Aaron tried to keep his thoughts at bay by busying himself with making a pot of potato soup—his mother’s favorite kind. He lit all the lamps, built up the fire blazing hot and set the table for two, with the wooden spoons she’d carved herself and her treasured blue-enameled bowls—as if to lure her in out of the darkness.

He decided not to eat until she arrived. He waited an hour. Two hours.

Surely she’d just gotten a late start this morning, or been merely slowed down by the snow. Why, she was bound to show up, and any minute at that.

Another hour passed. At last Aaron couldn’t wait any longer, and he ate his dinner alone. He was ready to fall asleep in his chair but he refused to turn in, forcing himself to stay awake. He cocked his ear to the sound of the snow scratching against the windows like a cat, desperate to make of it horses’ hooves and the sound of wheels turning.

Finally he could keep his eyes open no longer. He rose from his chair, made certain the door was shut tight, but left it unlatched. He placed a lamp before the window that faced the road, turned it down low and looked out one more time. Then he climbed into bed, and fell asleep waiting for the sound of a wagon.

At dawn he awoke with a start, sprang out of the sheets and stopped in his tracks. His mother’s bed was still empty.

What could have happened? He’d been certain she’d be there in the morning, sure she’d have arrived during the night, creeping inside quiet as a mouse, careful not to wake him.

Aaron ran to the window and looked out. He peered through the snow still falling from the sky, but nowhere was his mother to be seen.

He glanced around the room, and noticed her thick winter coat on the rack by the door—she hadn’t thought to take it along. Suddenly, everything she’d warned him of leaped into Aaron’s mind, and he was struck with the fear that she wasn’t just late—but that something had happened to her.

Could she have lost her way in the woods, with the roads covered with snow? Had the wagon become mired in a drift? Had she been attacked by a wolf pack, or a bear, or been fallen upon by thieves? Was she lost in the snow somewhere this very moment, shivering in the cold, calling for help?

He remembered what she’d said about leaving sight of the house. But surely she hadn’t meant for him to stay home at a time like this. Perhaps she was stranded just a mile from home. And if she were still close to Craftsbury—why, he’d ridden those roads every month of his life. He’d find his way through the forest, sure as an owl. After all, his birthday had passed, he was a full twelve years old—and she’d expect him to act it.

He rushed about the house, found a large burlap sack and filled it with food, enough for himself and his mother for several days. He packed his flint, a pot and a spoon, paper, pen and ink. He put on his scarf and his mittens and brought his mother’s along, drew on his plaid wool coat and put her own coat

on over it, so she’d have it to wear. He stood in the center of the room, glancing nervously about, looking for anything he might have forgotten. Then he walked to the door, and set out to find her.

3

Up the road Aaron marched, with the snow knee-deep on the ground now and still blowing down from the clouds. His feet felt pinched, for he’d outgrown his boots, and the wind numbed his face till it felt like stone. The sound of the sea faded as he tramped along, the sack slung over his shoulder and his mother’s coat dragging in the snow.

At last he arrived at the edge of the forest, passed in among the trees and came to a fork in the road. He bore to the right, just as he remembered his mother doing, and sharpened his eyes for any sign of her. Deeper into the woods he walked, the trees leafless and bare and their tops swaying in the wind. Soon the road divided again, and again he bore right. Hour after hour he trudged through the snow, treading his way through the maze of the woods, stopping to eat when his stomach grew empty and moving on through the forest again.

It was late afternoon when Aaron came to another fork in the road and stopped, looking about in bewilderment. He struggled to find something familiar to seize on, but nothing he saw set his memory in motion. He stared at the sky, at the trees and the road, and realized that riding along in the wagon was different from guiding it. He turned and looked about for the ocean, but it was nowhere in sight. He climbed up a tree, and saw only more trees, stretching endlessly to the horizon in every direction.

He cursed his memory but vowed not to turn back. He took note of the wind and the path of the sun—and suddenly felt certain that he ought to bear left, and struck out up the road.

The wind swept angrily out of the sky, driving the snow in his face and moaning two-voiced through the trees. Onward he trudged, the road twisting like an eel and growing ever more narrow, while the branches gesticulated wildly in the wind, as if desperately struggling to be understood.

Snow streamed down, filling in the trail of footprints behind him, and slowly the light began to fade. Soon the road tapered down to a trickle so that Aaron had to search for it anew every few steps. Still he pushed ahead, tired and hungry, groping for the trail among the trees.

Joyful Noise

Joyful Noise The Half-a-Moon Inn

The Half-a-Moon Inn Rear-View Mirrors

Rear-View Mirrors Saturnalia

Saturnalia Zap

Zap Graven Images

Graven Images A Fate Totally Worse Than Death

A Fate Totally Worse Than Death Whirligig

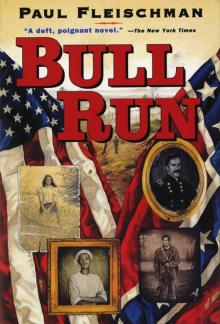

Whirligig Bull Run

Bull Run