- Home

- Paul Fleischman

Saturnalia Page 2

Saturnalia Read online

Page 2

“Be off!” shouted Malcolm, moving up beside his master. He would turn twenty in a matter of weeks, old enough to be his own master, and had increasingly found the role of lagging lackey insufferable.

“Off now!” The dog dropped back; Malcolm stayed.

Mr. Hogwood cast him a look full of meaning. What use was there in parading your man if he humiliated you in public?

“Beware of yonder goats,” said Malcolm solicitously, justifying his presence. He slowed his long legs to match his master’s pace. “Mrs. Mott’s shop’s on the left, past the pump,” he added, as if Mr. Hogwood didn’t know. In further display of his services, he scouted a patch of treacherous footing, sent scurrying a succession of pigs, and defended his master from a foul-breathed fishwife before flinging open Mrs. Mott’s door with a deference verging on mockery.

A savory braid of scent reached his nose, woven of fruitcakes, lemons, and wines. His eyes took in the equally pleasing sight of Mrs. Mott’s comely shopgirl.

“Six of your sweetest oranges,” said Malcolm. He grinned, his teeth glinting like winter stars, and received a modest smile from the girl. Finding his master scrutinizing the rums and brandies, he approached her more closely. “Plus a half pound of raisins,” he whispered, then winked. The girl nodded knowingly. Malcolm took stock of her body’s many advantages while she stooped for the one item and ascended a short stepladder for the other. Paying for both, he promised to return the favor at a future date, winked, and nearly yanked the door off its hinges in honor of his master’s exit.

“The cost?” asked the wigmaker.

“One shilling tenpence,” Malcolm answered truthfully. He’d found that Mr. Hogwood kept track of the money entrusted to him for purchases, and that each missing penny had to be accounted for.

His master stopped short. “For a mere six oranges?” He held down his hat against a thieving gust of wind.

“The girl said they’re extremely choice,” explained Malcolm. “Brought all the way from Spain.” The wigmaker snorted He moved on again, as did Malcolm, at his side. “And ’tis sure you want the choicest to be found. Considering who’s to receive them.”

Mr. Hogwood angrily flapped his hand, motioning Malcolm back two paces, from the safety of which position the servant commenced to feast on the raisins in his pocket.

Following the path worn through the snow, Mr. Hogwood mused on Malcolm’s words. He was right—this was no time to think of expense. Madam Phipp, after all, was accustomed to fine foods. In winter she probably dined every day upon sweet-smelling fruits from the earth’s four corners, rather than on beets from the root cellar, like most. Nevertheless, he imagined her gobbling up all six oranges at a sitting, enchanted by their taste and aroma, gratefully murmuring his name. It would be his first proper courtship gift. Malcolm, who appeared quite learned in such things, had particularly recommended oranges. Mr. Hogwood hoped his advice was sound. Widows, he knew, didn’t stay widows long. Her home had likely been swarmed by men at the news of her wealthy husband’s demise. As if God had meant Mr. Hogwood to make the most of this chance for social advancement, he’d plucked Mrs. Hogwood off the earth the next week. And though he’d long sneered at his wife’s common forebears, the wigmaker had been pleased by the sum, inherited from her grandfather, that had come to him upon her death—which money he’d invested in the fine clothes on his frame and the servant at his stern.

“’Tis Madam Phipp’s bakeshop on the left,” declared Malcolm, discreetly advancing to his master’s side.

Mr. Hogwood glared at him and wondered how it was that he seemed to know everything. A passing woman flashed Malcolm a smile. And everyone, the wigmaker added. Envious of the scamp’s handsome features, he shooed him to the rear, then saw Mr. Baggot approaching and haughtily raised his head. “Devilish bushes of vanity” was the tithingman’s stock pronouncement on wigs. He was one of a weakening wig-hating faction, several of whom over the past months had furtively made their way to Mr. Hogwood’s to have their heads shaved, measured, and re-covered. He glanced at Mr. Baggot’s own hair as they passed—grimy, flame red, pathetically sparse—and smirked at the ludicrous sight. Poor man!

“Madam Phipp has her shoes repaired here,” spoke up Malcolm, slipping forward yet again.

Mr. Hogwood scowled at his manservant.

“Of course,” he went on, “her new shoes come from England. Purchased by her sister-in-law in London.” He led his master around a mound of dung, brushed some snow from his beaver hat, and kept his place by bubbling forth more news of Madam Phipp up Water Street, down Cornhill, past the Town House, and back to their shop at the head of King Street.

Malcolm majestically opened the door, and Mr. Hogwood’s journeymen and apprentices instantly jerked to life like string puppets, blowing away crumbs, leaping from naps, and setting furiously to work with needle, curling iron, and comb.

“Any tidings of import?” the wigmaker asked.

All but one shook their heads “no,” as if they were too immersed in their tasks to spare the use of their tongues.

“Charity snared another mouse,” piped up Dan, Mr. Hogwood’s young nephew and newest apprentice. Just come to Boston the day before, knowing nothing of the wigmaking trade, he’d been given house chores and immediately had dropped a log on his uncle’s toe. Frantic to impress his snarling master, he’d taken upon himself to rid the ceilings of cobwebs in his absence this morning, managing to fall but twice and to break no more than six mugs and one chair. Hoping to please further, he now pointed out the latest mouse’s head left on the floor by the shop’s industrious cat.

“At least someone here earns his keep,” snapped Mr. Hogwood. He signaled Malcolm to remove his cloak. “Have you sluggards left it on the floor all morning?”

Dan darted forward and snatched it up. “Where would you have me put it, Uncle?”

“Anywhere, thickwit!” thundered Mr. Hogwood. “Just take it away ere a customer comes!”

His nephew vanished with it in his hands, while the wigmaker wondered how such a wormy fruit had appeared on the family tree. Six years he’d have to endure the boy! Trying to calm himself, he approached the featureless wooden head that held a wig belonging to Madam Phipp’s footman, returned to the shop for a routine dressing. Mr. Hogwood picked up a tortoiseshell comb. Though its wearer was male, the wig’s brown hair had come from a woman, females’ hair having been found to be stronger than men’s. Rounding curls, shaping, straightening, his fingers moved up one row and down another, as if laboring in a garden of hair. Gradually, his thick lips formed a smile. He began to hum and felt his cares retreat, replaced by the pleasing fancy that he was running his hands through the ravishing chestnut locks of Madam Phipp herself.

A gentleman entered the shop to be shaved, followed by another to have a tooth pulled. A burly hair merchant paid a call and filled the wigmaker’s order for more flaxen, black, and gray hair from England. Finishing with the footman’s wig, Mr. Hogwood took one of the sheets of paper bought at the printer’s shop that morning and snipped it into quarters with his scissors. He folded one of the quarters in half, dipped a pen in ink, and wrote “With the Special Compliments of Samuel Hogwood, Wigmaker, King Street, Boston.” Opening the door to a wig box, he draped the wig over the stand inside, then added the card, something he did only with wigs from Madam Phipp’s household, to no perceptible effect so far. Malcolm then served him the cook’s noon meal of boiled parsnips, codfish cakes, and apple slump, washed down with the beer it was a manservant’s duty to brew in the cellar. Having yet to master this craft’s finer points, along with several of its major principles, Malcolm noted Mr. Hogwood’s grimace upon his first swig of the potent concoction, and his loss of concentration on his food after six or seven more. Belching, the wigmaker rose from the table, squinted, searched his yeast-clouded wits, and just succeeded in remembering, on his way upstairs for an unaccustomed nap, to tell his manservant to

deliver the wig and oranges to Madam Phipp that afternoon.

“Yes, sir,” answered Malcolm. Abhorring waste, and cold cod, he quickly finished his master’s meal while the food was still warm. After eating the same fare again with the other members of the household, he divided the oranges among his pockets, took up the wig box by its handle, and set off.

Gaily, Malcolm whistled a tune. When alone on errands he felt gloriously free, at no one’s beck and call but his own. Then again, he reflected, picking up an orange, this outing was another proof of his slavery—for why else had Mr. Hogwood sent him but to impress Madam Phipp with the fact that he now had a servant to tramp the streets in his place? The wig box in one hand, he held the orange to his mouth with the other, peeled it with his teeth, and cast the skin to a pig. His mood gone sour, he sweetened his mouth with the heavenly juice and began to feel better. For months he’d been craving the taste of an orange, and he thanked his suggestible master for satisfying his desire.

He stopped before a dressmaker’s window. Appraising his reflection in detail, he adjusted his wig, straightened his hat, inspected his smile, cleaned out both nostrils, ignored the rude gestures of the woman within, and continued two doors down to a cookshop. There he traded an orange to the owner’s alluring daughter for a glass of ale, a squeeze of her hand, and a smuggled leg of lamb. Explaining that he had an errand to accomplish, he strode off in the direction of Boston Neck, made his way to a merchant’s rear door, and was asked in by a serving girl of his acquaintance. Over three glasses of pilfered wine, the two warmed themselves at the hearth and traded gossip of their respective masters. Before leaving, due to the press of his duties, Malcolm presented the girl with an orange, described its journey from Spain and great cost, and extracted two kisses in recompense. He traveled on and happened to meet in the street a stony-faced shopgirl he knew. Assuring her that she alone owned his heart, he found her doubtful, saw that the orange he’d planned to bestow would most likely be squandered, ate it himself, and at last reached Madam Phipp’s.

The house was of brick, many-gabled and grand. He glimpsed a black servant unhitching Madam Phipp’s gleaming carriage from her matched team of horses. He ascended the steps and rapped loudly with the knocker. African slaves, a coach house for her carriage, a chandelier hanging over his head . . . Malcolm’s calculation of the woman’s worth was interrupted by the opening of the door.

“Yes?”

He grinned at the serving girl before him, brown-haired and big-eyed and unknown to him. “Malcolm Poole at your service,” he stated. He inventoried her sleek body with a glance.

Knowingly, the girl eyed the wig box. “At my service, and someone else’s, I warrant.”

The manservant parried this thrust with a smile. “’Tis true that I recently engaged myself to Mr. Hogwood, a wigmaker,” he conceded. This was his euphemism for the fact that his master had paid for his passage from England and was due five long years of Malcolm’s labor in return, all but nine weeks of which he still owed. “That service, of course, pertains solely to the body,” Malcolm elaborated. “My service to you pertains to the soul. That soft-voiced master within your breast, for whom I—”

His speech was cut short by the girl’s grabbing the wig box and slamming the heavy door on his quickly inserted boot.

“Whom ’twould be utter rapture to serve,” he continued through the narrow opening. “Who bellows not for more stew or a hotter fire or to have his boots tugged off. But who asks of her servant only love.” His hands reached quickly into a pocket. “As a sign of my allegiance, I’d like to present you with a small gift.” He considered giving her both remaining oranges, then remembered that it was in his own interests to keep Mr. Hogwood’s courtship alive, that the flow of gifts, so useful, might continue. Feeling one fruit and then the other, he drew out the larger, handed it through, and heard it fall on the floor.

“My master also wished me to leave a token of his regard for your mistress.” Though the girl was thin, so was his boot leather, and Malcolm found her pressing with such force that he had to deftly substitute his other foot in the door. Digging out of his waistcoat pocket the last, smallest, and hardest of the oranges, Malcolm heard the serving girl strain, feared he’d soon be crippled, and tried to deliver the fruit while withdrawing his foot—with the unfortunate result that Madam Phipp’s gift was crushed in her doorway, splitting its skin, spurting forth juice, and spitting its seeds in all directions, two of which struck Malcolm on the nose before he fled down the front steps in retreat.

The girl, he concluded while hobbling home, was not entirely in his grasp. Yet.

TWO

BY HALF PAST FIVE THAT AFTERNOON the stars shone over Boston. By six o’clock shops were shut tight for the night. By seven thirty a great many of their owners had digested their dinners, read from their Bibles, and heated their sheets with the warming pan. In place of the sun, the light atop Beacon Hill now watched over town and harbor with its unblinking, oil-burning eye. Day birds dreamed. Owls awakened. And Boston’s nocturnal citizens emerged.

Night watchmen relieved the town’s nine constables. In the Common, three pairs of couriers, hearts sizzling and noses frozen, strode briskly through the snow. A runaway eyeglass maker’s apprentice, his pockets bulging with rolls, dashed up Pond Street, then headed toward the town gate. While in front of the Mermaid Tavern, on King Street, Mr. Benjamin Henry Tillstone, known as Tut, unfolded the wooden stand for his telescope.

“Penny a peep!” he informed the world at large, a world uninhabited at the moment except by himself and his dog curled nearby. A bustling man, small and lean as his whippet, he sunk the stand’s legs into the snow, attached the three-foot-long telescope, and inspected its swivel. “Penny a peep!” Working by the light from the Mermaid’s window, he produced this call, froglike, three more times in the course of cleaning the eyepiece with a cloth, busily polishing the brass barrel, and then training it on a light in the east. “Gaze through the glass at the planet Saturn!”

Two men left the tavern, one of whom stated his fear that should he look through the contrivance he’d at once find himself transported to the stars. The other, scoffing at such ignorance, paid his penny, viewed Saturn’s rings, and stormed away declaring the sight had been painted inside the instrument.

“Penny a peep!” Tut patted his dog, white as the snow on which she lay. Gently, he examined her splinted front leg. “Behold the marvels of God’s firmament!”

Four men in succession loomed out of the darkness of the unlit street, each passing Tut by. The telescope exhibitor sighed. Just as his name had suffered a shortening during his stint in the British Navy, so his fortunes had recently narrowed. Prone to put the best face on things, he pulled out the night’s first coin, smiled, and gazed up at the sky from which it had come. The heavens were now his fruitful fields, the telescope his plowshare and sickle. Clouds were his locusts, and winter his summer, when the nights were long and the stars bright as diamonds. Blowing upon his ungloved fingers, he told himself that the cold months were a blessing. Especially since his career demonstrating sleights of hand with cards and dice had been abruptly brought to a close three weeks back, the result of a tithingman’s complaint that had led him to be ordered by a judge to find a more praiseworthy line of work. Turning to his dog’s talent for tricks, he’d passed his hat at cookshops and groggeries while narrating, in a reverent tone, the canine’s tributes to the glory of God’s animal creations. This living had quickly ended with the dog’s falling from a pyramid of five chairs, snapping a leg and leaving her master as well without any means of support but the much-dented telescope before him.

“Penny a peep!” he addressed a pair of passersby, to no avail. He hugged himself against the cold, his ragged doublet and breeches offering the winter air a wide choice of entrances. Trying to breathe life into his fingers, he glimpsed the Mermaid’s hearth through the window and longed to be earning his living indoors

. Then again, he begged to differ with himself, his was a pleasant trade. Plenty of time to think your own thoughts, and none of the alehouses’ uproar and stale air. He looked up at Orion rising in the east and smiled, as at the approach of a friend. Then he spied three men trudging up the street and swiveled the telescope to the north.

“I’ve Andromeda in the glass for your pleasure! Chained to a rock to be eaten by the sea monster. Saved by Perseus riding his flying horse. All for the price of a penny!” The men, jabbering in a foreign tongue, warily avoided Tut, leaving him staring down at his dog. But for you, he brooded, we could both be warm as coals. And yet, he pointed out in reply, you learned quite a lot with the telescope. Taking the advice of the nautical instrument maker from whom he’d bought it third-hand, he’d purchased a book on the constellations and had increased his business a good deal by describing the shocking goings-on overhead, which deeds a certain percentage of his patrons expected to actually witness through the glass.

Two rum-sodden sailors staggered out of the Mermaid.

“Princess Andromeda, comely as a May queen, here in the glass!” beckoned Tut.

The first one succeeded in stopping his legs. “Bonny wench, is she?” he slurred with some interest.

“Ask her if her pa’s at home,” barked the other, bumping blindly into his companion. “Don’t want any bother from him, do we now?”

Joyful Noise

Joyful Noise The Half-a-Moon Inn

The Half-a-Moon Inn Rear-View Mirrors

Rear-View Mirrors Saturnalia

Saturnalia Zap

Zap Graven Images

Graven Images A Fate Totally Worse Than Death

A Fate Totally Worse Than Death Whirligig

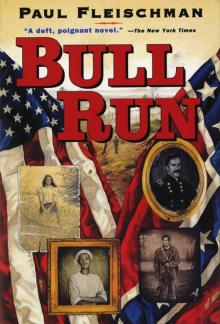

Whirligig Bull Run

Bull Run