- Home

- Paul Fleischman

Whirligig Page 2

Whirligig Read online

Page 2

“Calling Miss Manners,” someone shouted out.

“Tell her it’s an emergency.”

“Y’all come back, Georgia boy.”

He entered the house, his thoughts swirling. He took a wrong turn, passed through the dining room twice, kicked a wall in frustration, then charged down a hall and found the front door. He left it standing open behind him and steamed toward his car like a torpedo. Jonathan could find another ride home.

He got in and peeled out. His mind was a wreckage of sound bites and images from the last five minutes, endlessly repeating, shuffled, overlapping. It didn’t seem real, but he knew it was. The consequences would be real as well. He was a leper now. No one would go near him. Certainly no girl. He’d destroyed himself.

He shot up an entrance ramp. “He forgot to tell me about the stupid clothes!” he yelled, and the tantrum began. “Some stupid, idiotic, goddamn friend!” He shouted out the catalog of the night’s injustices, rained punishments on his enemies, wailed at his disappointments and deprivations. The flood of words seemed to bear him down the road. His head reeled with drink and despair. Then he saw that he’d gotten on the wrong expressway. This was 94. They’d come on 294, or so he thought. He rummaged hopelessly through his memory, trying to recall their route. He’d let Jonathan guide him and hadn’t paid attention. He fumbled, opened the glove compartment, and let loose a landslide of cassettes. He felt around with his hand. No map. He was nearing Skokie. He began to get nervous. He wondered where 94 led. Then mile by mile the uneasiness passed. He felt strangely unconcerned. He realized that he really didn’t care where he was going. Why should he? His life was a house that had burned to the ground. What was there to go back to?

He drove on, weaving slightly, aware that every car but his had a destination. He felt spent, emptied of all will. He was beyond tantrums. Instead, a measured voice began broadcasting within him, soft and unexpected, like a warm wind out of season.

There’s no need to go home, said the voice. No need to go back to school on Monday. No need to go there ever again.

Ahead, car lights hurtled toward him just as in a video game. He was in the fast lane, steering between the white lights on his left and the reds on his right.

There’s no need to feel pain. You’ve already felt enough.

The driver beside him honked when Brent drifted into his lane. Brent ignored him.

No need to let them hurt you again.

The voice flowed through his veins like morphine. He wove between the lights, hypnotized.

You have the power to stop the hurting.

He removed his hands experimentally from the steering wheel for a moment.

No need to be a pawn.

He put his hands back. The driver beside him honked once more, then slid several lanes over and sped up.

They are the pawns. You are a king.

He took his hands delicately off the wheel again.

You have a king’s absolute power within you.

He held his hands in midair for several seconds. They shook slightly. Gradually, he lowered them and laid them lightly on his thighs. He stared blankly at the lights before him.

You have absolute power over your own life.

He saw that the car was drifting to the left. He felt his hands jerk, but kept them on his thighs.

You have the power to end your life. Now.

Very slowly, he closed his eyes.

Weeksboro, Maine

“Would you mind telling me where we’re going?”

“To a motorboat waiting in a cove,” said Alexandra, “ready to take us to a French duke’s estate on one of Maine’s countless islands, there to join his harem.”

“Dream on.” I bumped her off the shoveled sidewalk and into the snow. “I’m serious.”

“C’est une surprise,” said Alexandra.

“You know I’m taking German.”

“I also know you’re brilliant enough to figure it out.”

“And that I hate surprises.”

“Honestly, Steph. Relax!”

The clearest winter days are the coldest. I gave my scarf a third and nearly fatal wrap around my neck. “It’s too freezing outside for ouija walking.” An Alexandra invention in which you walk without any conscious plan, letting your feet go where they will.

“We’re not going ouija walking,” she said.

“The Nook is closed Sundays, so we can’t steal scenes.” Another of her amusements, consisting of ordering something at Weeksboro’s one restaurant, listening to the people at the neighboring table, then talking about what they’re talking about—carburetors, hysterectomies—completely ignoring them when they stare at you.

“We’re not heading toward the Nook, as you can plainly see, chère.”

We passed the Town Hall, fanged with icicles, and turned down Beech Street. “So where are we going?”

“Out to the point, near Pam McQuillen’s. To throw a lifeline to a friend in distress.”

“What friend?”

Alexandra smiled. “You.”

I stopped, but she didn’t. I caught up, skidding on the ice. “What are you talking about?”

She sighed, producing a cloud of vapor. “You don’t like surprises. You like certainties. Facts. An extremely dangerous side effect of having marine biologists for parents. So let’s look at the facts. First, we’re eighth-graders. We’re in our biological prime. In many cultures around the world we’d already be married and bearing children. Soon our beauty will fade. Very soon. Just look at Sheila Sperl’s older sister. Second, three weeks and six days ago, Trevor and I pledged our love to each other. Third, you remain unattached, as you’ve been all two and a half years of middle school. Fourth, it’s the Christmas holidays, a time known to be especially painful for single people like yourself. Fifth and last, and most important, we’ve been best friends ever since nursery school. Who else but me has written you a birthday poem for six straight years? And who else besides you shows up at the Great Books discussion group I started? I don’t want this to come between us, Steph. We have to find you a boyfriend.”

We turned down Bolton Road. I was stunned.

“What have you got waiting out there?” I pictured a selection of boys tied to trees and penned naked in cages. “And who says I even want a boyfriend?”

“If you won’t say it, then I will.” Alexandra pulled her cap over her ears. “Communing with the urchins and eels in your aquariums can’t be totally satisfying. It’s time to move up to warm-blooded creatures. Boys, I’ll admit, don’t satisfy all needs. It’s difficult to discuss Jane Austen with Trevor. Extremely difficult. That’s why I value you. But there are some things males do awfully well.”

“Like rape. Warfare. Water pollution…”

“And some things that you could do to attract them. Letting your hair grow out for one. Show me one Playboy model who looks like she gets her hair done by the U.S. Marines. Long hair is mesmerizing to male humans. This is the kind of science you should be studying.”

“Long hair is a hassle.”

“Life is a hassle. La vie est dure. But it’s worth it, right? You could also stoop to using makeup. Eyeliner. Blush. Something on your lips.”

“And look like some washed-up Hollywood star on the cover of the National Enquirer?”

I could see Alexandra roll her eyes. “Didn’t we have this exact discussion at sailing camp last summer? I’m telling you, the natural windblown look won’t get you very far. It’s strictly for the homeless and war refugees.” She sighed. “It’s as if you’re trying to repel boys. When we got to choose a language last year, you could have picked French, the language of love. Instead, you had to choose German, the most masculine language on the face of the earth. Honestly, Steph, a girl taking German might as well write ‘Gay and Proud’ on her forehead.”

“I don’t believe it.”

“Have you ever been asked out?”

I had no reply to toss back at her.

“And then ther

e’s your name.”

“And what’s wrong with that?”

“Nothing,” said Alexandra. “If you’d use it. ‘Stephanie’ says slinky and shapely. A perfect name to go with long hair. But when I hear ‘Steph,’ the first thing that comes to my mind is ‘strep.’ As in ‘strep throat.’ I’m being brutally honest with you.”

“Thanks. I noticed.” I jammed my gloves in my pockets. “Of course, since I’m not slinky or shapely, and in fact am puny in every department, with freckles and oily, drab, brown hair, ‘Steph’ seems like the perfect name for me.”

Alexandra was silent. She seemed to shrink into her parka, trying to be less tall, less blond, less beautiful. She kicked a rock.

“I’m sorry, Steph. Please delete this entire conversation.” She mimed pressing a computer key. “You’re incredibly intelligent, funny, loyal, another Marie Curie in our midst, and any bonehead boy who doesn’t see this is a total idiot.” We passed by the McQuillens’ house. “Fortunately, the method we’ll be using should attract a male who’s worthy of you.”

We could now glimpse the bay in the gaps between the spruces. We turned off the road toward an abandoned house.

“What about the ‘Keep Out’ sign?”

“You mustn’t take everything so literally, Steph.” She blazed a path down the unplowed drive, punching her boots through the foot of snow. “And despite my praise for your intelligence, it would be best to leave your literal, logical mind behind at this point.”

“Hey, no problem. Call me Lucille Ball.”

Gulls squawked mockingly above. We passed the empty house, its white paint peeling and half its windows boarded up. We tramped between a clothesline and a shed leaning drunkenly to one side. The water was in full view now, an icy wind plucking at it and turning my face to stone.

“So why are we here, of all places?”

“That’s why.” Alexandra stopped and pointed at a strange contraption near the edge of the cliff.

“What is it?”

We approached. It was as big as a box kite and mounted on a pole, gesticulating wildly with moving arms, vanes, wheels, and propellers large and small. I’d never seen it. It was all different colors. It didn’t resemble anything in particular, except at the top, where there was a woman’s head. Attached to her hair were three reflectors. Shells and chimes hung around her neck. Even with half the moving parts stuck, a gust blowing through it set off a flurry of fluttering and shimmering and ringing, as if a flock of exotic birds was taking flight.

I squinted my eyes against the wind. “Who made it?”

“I think we can rule out the Pilgrims. How should I know? It’s always been here.”

“What’s written on the wood?”

“‘Lea Rosalia Santos Zamora.’”

“What’s that?”

“I’m pretty sure it’s a prayer to the wind.”

“And how is this thing going to get me a boyfriend?”

“It isn’t.” Alexandra pulled a paperback book from her back pocket. “But this will.”

She handed it to me. It was called Guided Imagery for Successful Living. I gawked at her. “You’ve got to be kidding.”

“Do you even know what guided imagery is?”

“No, but I know I don’t like it.”

“You said the same thing last year about boiling down Pepsi and pouring it over ice cream. Now you love it.”

“This is different.”

“Then you can forget what I said about Marie Curie. She believed in the scientific method. Observation, hypothesis, experiment—”

“So what’s the hypothesis?”

“That thoughts are powerful. That they’re the seeds of events. That by thinking something, we can help make it happen.”

It was my turn to roll my eyes. “I can’t believe you found a way to link Marie Curie with this mumbo jumbo.”

“This is not mumbo jumbo.” She took back the book and struggled to turn the pages with down mittens on her hands. “Here. Listen. ‘All that is, is the result of what we have thought.’”

“Wow. I’m convinced. I want to join your cult. Unless we have to pierce our noses.”

“That was written, for your information, by an ancient Buddhist monk.”

“Named Yogi Berra.”

“Stop it, Steph! This is serious!”

“I’ll say it is, if I get frostbite standing here. Why can’t we talk this over somewhere else?”

“Because this is the perfect place for guided imagery.” She pointed at the flashing whirligig. “You can’t see the wind, but look what it can do. It’s invisible but powerful. Like thoughts. One brings a bunch of junk to life. The other brings desires to life. And it’s better if you broadcast your thoughts outside. I did a visualization in this exact spot about acing an algebra test, and it worked. I’m sure it’s because of the whirligig. It symbolizes all unseen forces.” She stared at me. “It’s like electricity—an invisible power that people didn’t know existed for centuries. If you learn to use thoughts, you can do all kinds of things.” She flipped through the book. “There are visualizations here to make you resistant to illness. To overcome stress. To build confidence.”

“Let’s hear it.”

Alexandra stamped down a circle of snow and sat. I did the same, leaning my back against hers.

“‘Seek out a comfortable, nurturing place. Feel the gentle air against your skin.’”

“And your butt freezing to the ground.”

“‘Perhaps you’ll choose a quiet room or a peaceful corner of a garden. Breathe deeply. Feel yourself relax. Now feel the inner strength within you. Imagine this strength is a mighty river.’”

“Or for those with low confidence, a drip from a faucet.”

“‘We’re going to take a journey down this river.’”

“But remember—do not drink the water.”

She threw down the book. “I’m trying to help you!” She dumped a handful of snow on my head. “But your scoffing, scientific mind won’t let me. Secretly, you want to be an old maid. ‘Despite her seven Nobel Prizes, the eighty-eight-year-old spinster was in contact with neither friends nor relations. Her decomposed body had apparently been lying on her laboratory floor for years. The corpse was identified through dental records.’”

“Now there’s some imagery I could go for. Seven Nobel Prizes!”

“Laugh your head off.”

“Listen, Alexandra. I’m sorry. But it’s too much like those men on TV who bend spoons with their thoughts.”

“That’s quackery. This isn’t.”

“And are you going to tell me there’s a fantasy in the book that attracts boyfriends?”

“Not exactly. I thought I’d create one just for you. You don’t need a book. Anyone can lead a visualization.”

“It’s too cold and windy.”

“The wind helps, don’t you get it? It’ll carry my words away like seeds and plant them in the future.”

“You are a true mush-headed dreamer.”

“Thank you. And you’re a closed-minded skeptic. Now what do you say?”

“Either I say yes or I freeze to death arguing. Make it fast and let’s go.”

“Great!” she said. “But you wouldn’t want me to skimp on details, would you? I mean, we’re deciding your future here. You don’t want the standard L.L. Bean WASP boyfriend, in plaid or navy. You want someone designed just for you.”

“It’s you I’m doing this for, not me.”

“Have faith, mon amie. Okay. Close your eyes.”

We were back to back, so she couldn’t see me. I obeyed anyway.

“It’s summer. July.”

“Must be a cold spell.”

“You feel the balmy air on your skin as you complete your pleasant morning’s sail and tack into Portland’s harbor. Your hand is on the tiller of the sixteen-foot, all-wood, gaff-rigged sailboat your parents have bought you. Painted across the stern is the name you’ve chosen for it—Free Spirit.”

&n

bsp; “Why not Hunk o’ Love and my phone number?”

“Shh! You’ll wreck it! You tie up at the dock. You haul down the sails and check the specimens in the holding tanks you’ve fitted it out with. You step ashore, your waist-length hair waving in the breeze like kelp.”

“Guys really go for kelplike hair.”

“Would you shut up and listen for a change!” She paused, seeming to search for what to have happen next.

“Leisurely, you make your way up to Belk’s department store. You enter and glance at the perfumes, then know that the confidence and beauty you project is more potent than any scent. You go up two floors and try on a gorgeously embroidered French sundress. It is not on sale. You buy it anyway and decide to wear it. Next, you drift into the lingerie department. You approach the bras, find the 28s, and don’t stop until you reach the D cups.”

“No!” I said. “That’s too big!” I opened my eyes to see if the wind had already carried off this request. The whirligig was spinning merrily.

“You buy one. The scrawny saleswoman gives you an envious glare. Then you exit the store, stroll three doors down the block, and enter a coffeehouse. Your parents have encouraged you to drink coffee to slow your amazing growth—in this year, you’ve shot up to five-eight-and-a-half. Standing in line, you feel male eyes upon you. You turn and see him. He’s tall, like you. His neck is as thick as a tree trunk. He glances back at his Sports Illustrated. His lips move not only when he reads, but when he looks at the photographs. A Neanderthal. You avert your eyes. You get an iced coffee and take a seat far away.”

“My teeth are chattering like maniacs and I’m supposed to imagine drinking iced coffee?”

“Quiet! You pick up a French newspaper from an empty table and begin to read. Fluently. Through an intensive course on videotape, you’ve mastered the language in record time. Last night, you realize, you had a dream in French—powerfully erotic, drenching you in sweat. A man now approaches.” She paused, deliberating. “He’s wearing a beret. He’s handsome, young, and speaks to you in French. You instantly detect his faulty pronunciation of the French r. Then an incorrect participle. He’s a coffeehouse cad, a pickup artist. You send him away with a brisk ‘Laissez-moi!’”

Joyful Noise

Joyful Noise The Half-a-Moon Inn

The Half-a-Moon Inn Rear-View Mirrors

Rear-View Mirrors Saturnalia

Saturnalia Zap

Zap Graven Images

Graven Images A Fate Totally Worse Than Death

A Fate Totally Worse Than Death Whirligig

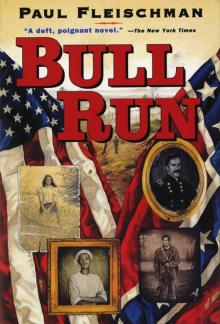

Whirligig Bull Run

Bull Run