- Home

- Paul Fleischman

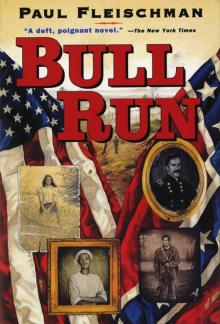

Bull Run Page 4

Bull Run Read online

Page 4

* * *

A. B. TILBURY

* * *

The guns did fairly roar before us. Our drivers raised a fine roar of their own, swearing and snapping their whips to bring our fieldpieces into position. There were six guns in our battery, with eight men to a gun. We labored hard and fast, firing solid shot, then switched to shrapnel. Our mothers soon wouldn’t have known our faces, black with powder and running with sweat. “May God have mercy on their guilty souls,” our lieutenant would shout, then yank on the lanyard. I had little leisure to watch the shells fly and could scarcely make out the Rebels for the smoke. Then I saw that the gun crew beside us was pointing. The enemy lines had broken and the men were scattering like rabbits. We were ordered forward. Didn’t we crow! “They’re whipped!” “Look at ’em all skedaddle!” “We’ll hang Jeff Davis!” “The war is over!”

* * *

DR. WILLIAM RYE

* * *

I lay on the grass, listening to the battle. Another doctor stood nearby, and two or three assistants. We were before a church, some miles from the fighting. Bees buzzed loudly from a hive nearby. A mockingbird went through his program, his song an unending river of gladness. Our ears, however, were cocked toward the distance. The first great battle of the war was taking place over the next hill. We knew the first wounded would shortly arrive. We’d set up two tables and readied our tourniquets, forceps, scalpels, and saws. We waited.

* * *

EDMUND UPWING

* * *

As the day was heartlessly hot and humid, I sat in my coach to keep out of the sun and exercised my jaws on a roll. My passengers’ menu reached my nose and eyes but not, alas, my stomach. Virginia ham, softshell crabs, Chesapeake Bay oysters on ice. Some dined on pheasant. ’Tis a fact, bright as brass. They squinted at the smoke now and then, then returned to the clash of knife and fork. All at once an officer of some sort galloped up our way. “We’ve whipped them on all points!” he cried out. “They’re retreating fast and we’re after them!” He charged off again. The air rang with cheers. My passengers were so moved by the news that they filled my old tin cup with champagne.

* * *

VIRGIL PEAVEY

* * *

We’d marched five miles and were perishing for water, then reached the battle and forgot we were thirsty. The balls whistled by us. It was a new sound to me. Jack, our mascot, a brave little bulldog, snapped at the bullets as if they were flies. I grabbed my friend Tuck to show him the sight, then saw he’d been shot straight in the heart. My own heart near quit. Then the call came to charge. I’d pledged to stay by him, but hadn’t calculated on him getting killed. Men scurried past. An officer shouted and shoved me ahead with the others. I dearly disliked leaving Tuck behind and suddenly felt all alone in the world. We got cut up awful and dashed back a spell later. Then we spied a gray regiment coming, almost fainted for joy, drew close by—and were killed by the cartload when they opened fire. It was Sherman’s men, gray-clad same as us. We cut dirt for our lives all the way to a creek. We formed a new line, but the shells and bullets fell upon us thick as rain. Men promised out loud to quit all their vices if only the Lord would spare their lives. General Bee glared back at Jackson, who was perched with his troops on a hill out of range. “He stands there like a damned stone wall!” he cried. “Why doesn’t he come and support us?” He let loose a deal of blasphemy. The next minute he was shot dead off his horse.

* * *

DIETRICH HERZ

* * *

My eyes opened and focused upon grass. I felt heavy and numb as a millstone. I was lying on the ground, tried to get up, but couldn’t make my head or limbs move. I felt wet about my legs, thought it must be from blood, but couldn’t tell where I’d been hit. I wondered how long I’d been lying there. The battle had moved ahead over the hill. I fixed my eyes on a man nearby. His eyes were looking straight back at me. Then I saw the red soaking through his shirt. Had the stretcher-bearers thought me dead as well? Was I wounded past helping? My head began pounding. “I mustn’t die here!” I told myself. I stared at the green grass before me with envy. Then I thought of the woman who’d sewn my shirt, whose note I’d never forgotten. Her photograph was in my jacket pocket. I had no family of my own in this country, and I’d thought and worried about her as you would about a wife or relation. I spoke to her now, within my mind. I told her we were both meant to live longer. I begged her not to take her own life. I described the tuft of grass before me. I asked her to help me live.

* * *

CARLOTTA KING

* * *

I was jump-stomached all day, wonderin’ who was winnin’. Past noon a soldier came wanderin’ our way. He’d been shot through the ear and held a kerchief up against it, drippin’ blood. I’d washed out all the master’s clothes and was sittin’ with the other slaves. He told us the Southern men were licked. I could hardly keep from yellin’ for joy. I wouldn’t have to run off to the North—the North was marchin’ down to me! Some cannons fired just then, and I thought, The Lord’s smitin’ the South at last! The soldier shucked off his pack and sat down. He took out a mirror and studied his face. His ear had a rip. He almost cried to see it. “The Confederacy’s finished,” he said. “And worse than that, my good looks is gone forever!”

* * *

GIDEON ADAMS

* * *

We weren’t far from the battle. It went quiet for a time, then struck up again louder than ever. I rejoiced at this. Finally, I felt sure, we’d be called to join the fight. I was wrong. We sat on the ground, an entire brigade of three thousand men, there by the stone bridge where we’d been sitting all day. Our role had been to fire a few shots and serve as decoys to mask McDowell’s main attack. Had I trained for months and journeyed a thousand miles only to pretend to fight? Had we been forgotten? I boiled with disappointment. While our comrades fought for freedom and the Union, the man beside me took aim at a turkey.

* * *

JUDAH JENKINS

* * *

I never did catch up with that horse. I soon found another without a rider. There was blood on the saddle. I wiped it off and wondered if a ghost weren’t watching me. We galloped back and forth, carrying orders and news, most of it bad. About noon I heard whistles at Manassas Junction. It was General Smith’s regiments. They were the last of Johnston’s men to make the trip from the Shenandoah. I was sent to tell them to hurry to the battle. The general saw the stragglers on the road, bleeding, crying for water, limping along or running for home like madmen. I told him the fight was all but lost. He ordered his troops to march at quickstep.

* * *

A. B. TILBURY

* * *

Twelve-pound balls, canister, shrapnel. We sent them all at the Southerners. Then their artillery took our measure and commenced to devil us in return. We’d fire and they’d fire. I expect they crouched when they heard a shell coming, same as we did. I almost felt I’d a double across the lines. I took to wondering whether their men were truly all savages, as I’d heard tell. They pulled back and hid their guns behind a house. Union shells ripped right through the walls. There was a woman inside, it turned out, and some of her kin. A man ran out, screaming “They’ve killed my mother!” over and over. I asked myself why soldiering was praised up as something to be proud of. We then pulled our guns to a hill far forward, with no infantry to protect us. We protested, but it was McDowell’s order. A line of men in blue marched toward us. Captain Griffin swore they were Rebels, but Major Barry swore even louder that they were our infantry support. There was no wind at all, so their flag hung limp. We couldn’t make it out, and held our fire. They came almost among us. Then the air exploded. That murderous volley dropped half our men and every last one of our horses. I was lucky to be struck only in both arms, leaving me free to run for my life.

* * *

SHEM SUGGS

* * *

We were mounted and waiting. We were tucked in the trees, ready to spring upon the Yanks. Jeb S

tuart was our colonel. He did love a surprise. He was even fonder of dressing up fine, and I thought sure his duds would give us away. Gold silk sash, gold spurs, white buckskin gloves, and an ostrich plume in his hat. He squinted out between the trees. The battle was almighty thick and hot. Finally, he gave the sign. He led us out of the woods and charged down into a line of Zouaves got up even gaudier than he was. They looked as frighted as if we’d ridden up out of Hell. There were cries and shots and smoke on every side. We were packed in tight. It was one great confusion. A Yank came at me with his bayonet. I jerked the reins left and he missed my leg. Then he aimed it at my horse. I shot him without thinking. I was amazed to see him pitch back, and gawked at the blood running down his side. I could scarcely believe I was the cause. I’d shot a man, a thin man with red whiskers. I might have just made his younguns into orphans, same as me. I felt shaky and shameful. We pulled back toward the woods. I found I was hoping the man would live.

* * *

GENERAL IRVIN McDOWELL

* * *

My flanking attack had succeeded superbly. Despite the delays, despite the fact that my men were no more than summer soldiers, despite the losses they’d absorbed, we’d driven the enemy backward all day. I paused for a time to re-form my line. I was then ready to deliver the death blow, ending the battle and the Confederacy both. Beauregard, though, had made use of the lull and had shifted many more men west. I ordered my artillery forward, to pound his line at close range. But the infantry who were to support them lost their way and were shattered by cavalry. Our gunners, through an error, were then slaughtered by the Rebels, who turned our cannons about upon us. We stormed the hill and reclaimed them more than once, but each time were forced to retreat. My men were collapsing from exhaustion and thirst. Some died of sunstroke in the fearsome heat. Fresh Southern troops, brought east by train, then reached the field, to great cheers from their comrades. I cursed old General Patterson anew. They fell upon us with their bloodcurdling yell. The right end of my line began to buckle. Then I watched it give way like a dam.

* * *

TOBY BOYCE

* * *

I didn’t reckon I could bear it another minute. The very battle I’d wanted a part in was booming just a few miles off, while I sat on a log and whittled a stick. The older Georgia boys who’d joined would come home loaded down heavy as peddlers with Yankee guns and medals and glory. And with scars to put on public display. I’d stare like the rest, quiet as a clam. I’d have been there as well, but would have to ask them to tell me exactly what had happened. The thought chafed me fierce. I snapped my knife shut. I stood up and snuck off toward the fighting.

* * *

JAMES DACY

* * *

It takes but a pebble to start an avalanche. The sight of some of our soldiers fleeing infected all the others with fear. Just at that moment, some Union teamsters drove their empty ammunition carts feverishly away from the battle and toward the rear, in full view of our men. They lashed their horses, no doubt that they might quickly return with supplies for our gunners. The troops, though, seemed to think them in desperate flight and concluded the cause was lost. Regiments suddenly ceased to exist. A vast tide of men began streaming from the field, slowly at first, then in a mad flood. My eyes were disbelieving. My thoughts swirled. These weren’t the same soldiers I’d sketched earlier. My notebook held heroes, marching in unison, bravely advancing, disdainful of death. I refused to draw the scene before me, or to sit idly by. I dashed toward the throng. I picked up a New York regimental standard flung down in the dust, and held it high. “Rally ’round, New York!” I shouted above the tumult. “Make a stand!” The men ignored me, surging past in a panic. I waved the standard back and forth. “New Yorkers, form up! Stand your ground and the day is yours! Why do you run?” “Because I can’t fly!” a voice called back.

* * *

COLONEL OLIVER BRATTLE

* * *

General Beauregard’s head finally cleared. He cast aside his original plan and galloped off to the battle at last. I rode with him. As new troops arrived, he fit them into our lengthening line. He heartened them in spirited fashion, especially during the worst of the fighting, riding up and down the ranks, praising the men, shoring up their resolve, instantly mounting another horse when his own was shot from beneath him. When we saw the Northerners starting to flee, he led our entire line forward in attack. President Davis arrived by train from Richmond in time to watch the rout. The speed of the Union collapse was astounding. Their soldiers left everything that might slow them. In a matter of minutes the ground they’d stood on held muskets, cannons, colors, packs, ammunition, blankets, caps—but no men.

* * *

EDMUND UPWING

* * *

The shout went ’round, “The Rebels are upon us!” The words struck the picnickers like a storm, sent them shrieking into their coaches, and sent every coach bolting toward the road. My riders commanded that I put on all speed. Each driver heard the same demand. The road was narrow and choked with coaches. This mass of wheels and whips blocked the soldiers, who seemed even more eager than we to be gone. They were furious with us. How their teamsters swore! Those on foot rushed around us like an April torrent. They were bloody, dusty, and wild-eyed as wolves. “The Black Horse Cavalry is coming!” one bellowed. The air rang with rumors of hidden batteries, heartless horsemen, rivers red with blood, and visions worthy of the Book of Revelation. One frantic soldier cut a horse free from a wagon’s team and took off bareback. Another fugitive tried to unseat me. I drove him off with my whip. ’Tis a fact. Then there came a terrific boom. Women screamed. A Rebel shell had fallen on the road. The caravan halted. The way was blocked by a tangle of overturned wagons. The soldiers scattered or froze in fear. Men fled their buggies. A second shell struck. Then a young officer galloped up, leaped down, and dragged the vehicles away. His courage was acclaimed. We jerked forward afresh. My sharp ear learned that the man’s name was Custer. All predicted that he was destined for great deeds.

* * *

CARLOTTA KING

* * *

A slave came and told us the Union was beat. My heart dropped like a bucket down a well. A while later the master’s friends came up the road, hootin’ and carryin’ on over the victory, noisy as jays. I couldn’t pretend smilin’ and just turned away. Then one of ’em told me my master was wounded and pointed where I’d find him. I gathered up a clean suit of clothes for him and some bandages and set off. Men were ridin’ or walkin’ every which way. I passed into the trees. Just some dead men there. I never did find my master. Never tried to neither. I told myself I couldn’t sit and wait for the Northerners to whip the South. And if Union soldiers sent slaves back to their masters, I’d just have to keep clear of ’em. I set down the clothes when I came to Bull Run. Then I waded across and kept movin’ north.

* * *

DIETRICH HERZ

* * *

I came to my senses some hours later. I was shaking with cold, though the sun shone upon me. I listened and heard a few shots, very distant. The sun was much lower. It seemed days since that morning. I didn’t think about the battle, about my regiment or my friends, but only of being found by someone. Then I heard a rustling. “A Barlow knife,” said a voice. “Got me two more pocket watches,” said another. My heart filled with hope. The ground shook around me. “Reckon I’ll be ticking worse than a clock shop,” the same voice went on. Then a hand reached inside my jacket. I felt the heat of the man’s warm arm. I found I could now move my own arm slightly, raised a finger to show him I lived, and spoke the words “Please help me.” The man gave a yelp. “Don’t go!” I pleaded. But he bounded away, dropping the photograph of the seamstress on the grass. I slowly moved my arm that way, a task that seemed to take hours, and at last dropped my hand upon it and cursed the plunderer.

Joyful Noise

Joyful Noise The Half-a-Moon Inn

The Half-a-Moon Inn Rear-View Mirrors

Rear-View Mirrors Saturnalia

Saturnalia Zap

Zap Graven Images

Graven Images A Fate Totally Worse Than Death

A Fate Totally Worse Than Death Whirligig

Whirligig Bull Run

Bull Run